Christmas comes early: Cusco kit swap

September 10th, 2013

If this journey has taught us one thing about kit over the past two years then it’s this: at some point, whatever the marketing hype and however much money you paid for it, it will break. Like our “expedition quality” Terra Nova Voyager XL tent, which fell apart in the Alaskan wilderness after just two weeks on the road. Or Sarah’s Rohloff – the “Rolls Royce” of gear hub systems no less – which had to be shipped to and from one of the only two places in the world where they could repair it when the hub bearings failed in Panamá.

It seems that when it comes to buying kit for really long trips, planning ahead for what happens when it breaks is probably just as important as how it actually works. Choosing kit that is as universal as possible – and so a lot easier to fix without shipping specialist parts around the world (ie, not a Rohloff) – is definitely a good start. One of my favourite things about Latin America is that the “fix it” culture which is fast disappearing from the supposedly developed world is still alive and kicking here. Whether it’s a failing tent zip, a beaten-up laptop, a seized bike part or a gaping shoe, head for the nearest market and chances are you’ll find a man or lady who can. These repair missions are always great fun too, taking us into parts of towns and cities where we otherwise would never have gone and meeting some incredibly helpful and skilled people. Time and time again on this trip, used and abused pieces of kit which we probably would have given up on long ago back home have been brought back to life.

However, there are still a few essential pieces of kit which we really have struggled to find on the road. Shipping spare parts around the world might seem like an attractive emergency option from the comfort of your home armchair, but in our experience it’s not quite that straightforward. Once you take into account the vagaries of Latin American postal systems, unexpected import taxes (try 40% in Colombia), and the difficulties of finding a secure address while on the move, it can work out much more frustrating and expensive than you might expect.

Enter stage left that long-standing lifeline of the kit-starved touring cyclist: the visit from family or friends. “We can’t wait to see you!” go the emails – and then, casually, as if it’s an after-thought – “Oh, and there might be just a couple of small things we need you to bring out for us – hope you don’t mind?” If you ever take up an invitation to visit a touring cyclist, just don’t expect to travel lightly. Chances are that by the time you set off to meet them, the “couple of small things” will have mutated into a full-blown expedition kit-list, and you’ll find yourself sawing the handle off your own toothbrush just to come in under your baggage weight limit.

For us, Dave’s visit to Cusco provided us with the perfect opportunity to replace a few of those hard-to-find parts, and to stock up on cold-weather gear for our next leg across the freezing Bolivian altiplano. Reports of night-time temperatures dropping to -20ºC from cyclists heading north had us scrambling to see if we could squeeze some new, warmer camping kit from the last drops of our kit budget.

And so, like a seasonally-challenged Santa Claus, our kit mule arrived in Cusco, heroically dragging behind him a sack of goodies…

James

Like any good Christmas, we began with some stocking fillers: a cyclist-sized Dairy Milk. Should keep our parasite friends happy for the next month…

…plus my special request: my first packet of salt and vinegar crisps in two years. Craving for Man Crisps suppressed for another year at least.

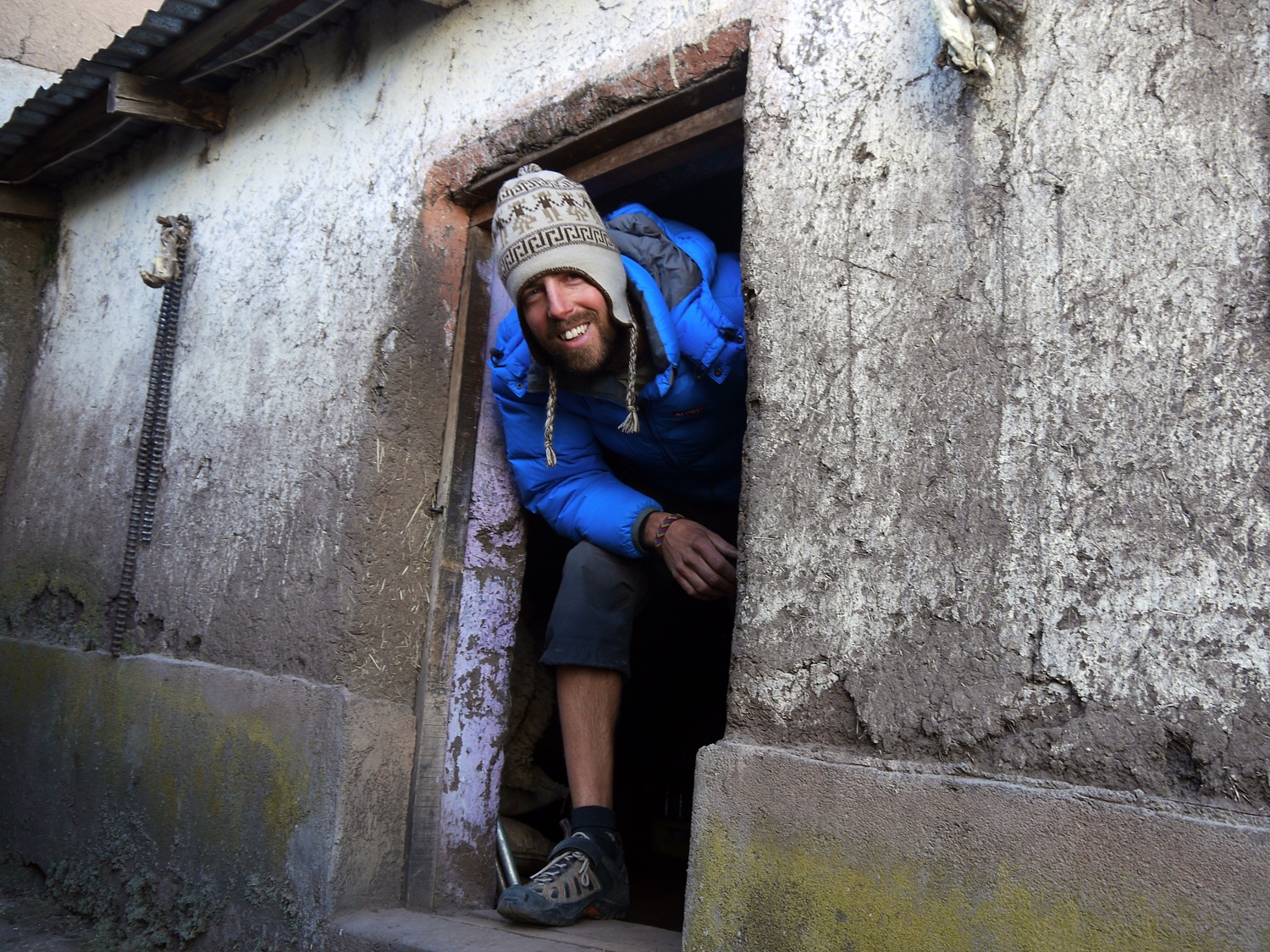

First priority was an overhaul of our camping kit. One by one, all four zips on our MSR Mutha Hubba tent had seized, calling for a serious of increasingly acrobatic manoeuvres to get in and out of the tent. We headed for a local seamster, who sewed in four chunky new zips and sliders in the time it probably would have taken us to unpick just one.

One too many shivering nights already in Peru had proved that our tired old sleeping bags weren’t really up to sub-zero temperatures. And so we decided to invest – two new Skyehigh 1000 bags from Alpkit, with a comfort rating of -13ºC. Not the lightest or most technical of bags, but more importantly they pack an impressive 1kg of down for a fraction of the price of the big brand names. As cold sleepers, somehow I don’t think we’ll be regretting these up on the Puna.

Next up, some extra insulation from the increasingly cold ground. Out with our trustworthy (but bulky) foam Ridgerests (a miserly 1.5cm thick), and in with two new Prolite Plus air mattresses (a luxurious 3.8cm thick). Meanwhile the old Ridgerests were put to good use…

…and recycled as perfect new protective cases for our Kindles and laptop. Lightweight, padded and made-to-measure – far better than anything you’ll find in the shops.

This is my second pair of Specialized Tahoe shoes so far on the trip. They’re a comfy compromise between trainers and “proper” bike shoes, but unfortunately have already started to split open at the sides. Luckily, shoe repair is easy to find in Peru – here a professional adds in the extra stitching that Specialized really should have put in from the start.

For a self-confessed friolenta (someone who feels the cold) like Bedders, it doesn’t get much better than hiding yourself in a down jacket – another Alpkit special. Somehow I get the feeling this might not be coming off much over the next 5 months…

…which is a shame when you’ve just invested in a new t-shirt as good as this one. Maybe I should put this publicly-pronounced love of the moustache to the test soon, just to complete my hideous facial hair quota for the trip.

A full drivetrain overhaul for the bikes: new front chainrings (after an impressive 25,000km), new rear sprockets (a lifespan of 12,000km with reversing) and new chains. Despite my moaning, Rohloff definitely has its advantages when it comes to easy maintenance – hopefully, these should see us through to Ushuaia and beyond.

After one soaking too many (and, if I’m honest, probably not enough Proofide), my trusty Brooks B17 had started to crack badly around a couple of rivets, and looked like it could tear off completely. Luckily, I found a leather craftsman who was able to replace the rusted rivet and apply a patch which hopefully will hold things together for a good while yet.

The most traumatic kit failure of the last few months was our beloved Primus Omnifuel stove. Two years of burning only petrol took its toll, seizing the control spindle and wrecking the thread. To their credit, Primus came good and sent us a new burner unit and spindle under guarantee – just unfortunately not in time for Dave to bring it out with him.

In the meantime, we had already been seduced by the shiny new titanium Primus Omnilite. Normally way out of our price range, incredibly we found it on special offer for the same price as a new standard Omnifuel, and snapped it up. This really is a dinky stove…

…but still with all the hallmarks of quality Primus construction. Looking forward to putting it to the test with some of that dirty Bolivian diesel.

After two years of stove-top coffee experimentation (with filters, “cowboy” style, brewed in a kids’ sock) – and having abandoned any pretensions of minimalism – we finally caved and bought ourselves a stove-top espresso maker. We might not fit in with the bikepacker crowd, but we can at least satisfy our morning caffeine cravings in style, and with a touch of crema…

Another over-worked piece of kit – our MSR MiniWorks water filter. When the ceramic filter starts to cave in the middle, like the one on the left, the bugs can start to get through and it’s time to change.

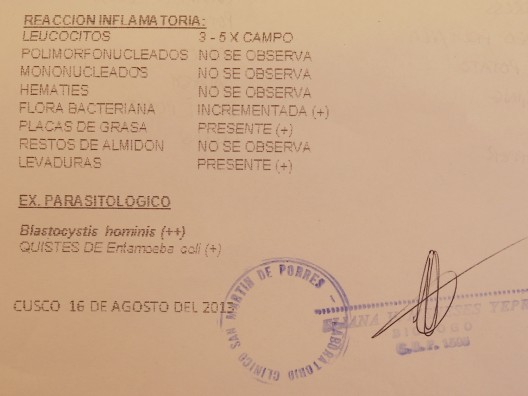

Speaking of which, Christmas wouldn’t be complete without the unwanted gifts. Our equivalent of the hideous knitted jumper from Great Aunt Matilda came in the form of a vicious return of our lingering parasitic friends, just as we were preparing to leave Cusco. This time we’ve really gone to war: a double dose of anti-parasitics, combined with a Hollywood-esque diet free from sugar, gluten, dairy and caffeine designed to starve them out at the same time. As I write this, we’re starting to feel better, and – fingers crossed – hope to finally be moving again soon.

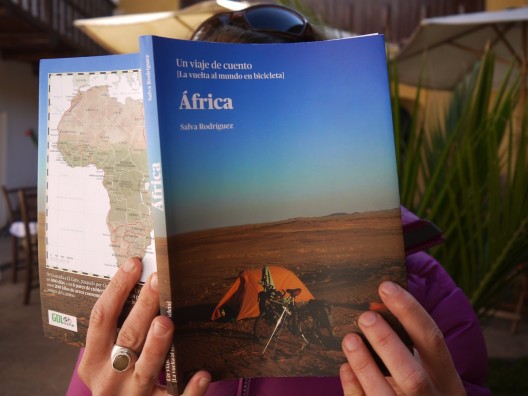

Every cloud has a silver lining however, and on the plus side it’s meant that we’ve got to share our extra Cusco downtime with our friend Salva and his girlfriend Lorelí. Plenty of time to get stuck into the excellent first book of his epic seven and a half year cycle round the world – leaving us itching all the more to get back on our bikes soon…

Leaving Cusco: an Andean antidote

September 20th, 2013

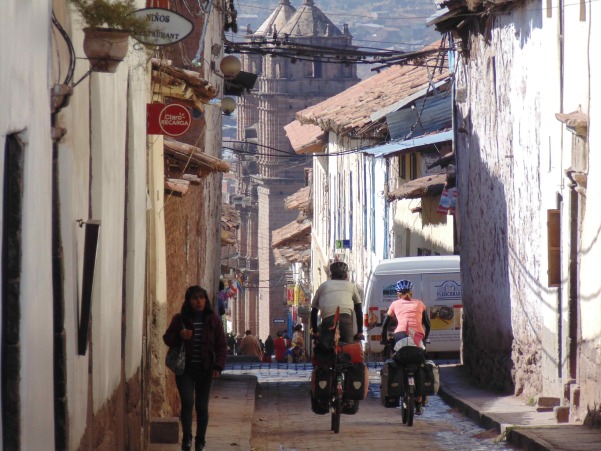

Having spent a month in the heaving streets of Cusco receiving visiting relatives and trying to repair our parasite-riddled bodies, finally it was time to leave fancy coffee, organised tours and Incan ruins behind and get back to some cycling.

Leaving Cusco was difficult in that we had to say goodbye to good friends and as always after extended time off the bikes, our legs had become soft, lazy and unwilling. The exit itself wasn’t without its challenges either. Leaving on the main road was ugly and not a route I would want to repeat in a hurry; red-mist descended quickly as Peruvian drivers proudly displayed their prowess in terrible driving, and both James and I came extremely close to losing both our tempers and our lives on more than one occasion.

Realising our mistake at spending more than five minutes on the main road, we turned off at the first opportunity and escaped back to our natural habitat – the campo. The Cusco antidote we had been looking for and our last foray into the Andes before the altiplano in Bolivia: fresh rarified air, legs burning at the first proper climb for five weeks, no traffic, snow-capped peaks, camping, speaking Spanish again…all of the ingredients needed to recharge the cycling batteries and shake off city life.

Sarah

…is to enjoy good coffee and flaky croissants at the French bakery on Avenida Tullamayo before we leave the city. Sadly the delicious breakfast can’t protect us from the carnage of the autopista…

…but soon we are off the main road and the only traffic we encounter around Acopia, and its four beautiful lakes, are bici-máquinas and donkeys.

On the pretext of admiring the view around the lakes, we stop frequently to rest our legs and take deep breaths.

Outside of Yanaoca, Marco (pictured right) screeches to a stop on his police motorbike to check we are OK and invites us to drop in at the police station to chat with him and his colleague Felipe…

…after cake and coffee with them, it’s clear we are not going any further that day. We set up the tent in the yard at the back of the police station but after much discussion amongst the force who decide it’s far too cold for us to sleep outside (despite our reassurances), we are ushered inside and given the honour of sleeping in the police dorm, in between official insignia stamped sheets and blankets.

The road turns to dirt after Yanaoca and offers the usual assortment of entertainment: alpacas so hairy they can barely see…

…and unexpected snacks – a lady stops us begging for a photo and in return gives us a bag of piping hot potatoes. Why anyone would want a photo of a sweaty gringo couple on their bikes is beyond me but the spuds are tasty. Peru has more than 150 varieties of potato of all colours, shapes and sizes…this pink one, teamed with salt and avocado, was delicious.

Back onto pavement briefly (joining a main road between Cusco and Arequipa) we hit dirt again and lots of flat, towards Hector Tejada…

A network of back roads in this area represents the chance to drop down to canyon country and Arequipa. Before we leave Cusco we toy with the idea of visiting the canyons, but have to abandon the idea when parasite destruction takes longer than expected. So from here, it’s straight ahead to Jauni and leave the canyon riding until next time.

We are again ushered indoors for the night when we reach the village of Jauni. Shopkeeper and generally lovely lady, Francisca, offers us a room at the back of her house…

The next morning we emerge into fierce sunshine to share freshly boiled eggs and chat with Francisca…

Land provides shelter – most houses here are made from mud taken directly from the earth – we pass hundreds of hand-made bricks laid out to dry in the sun.

A pleasant 7km downhill gets her from home to school in no time, but I imagine her return journey isn’t as much fun.

Our final major climb in Peru is a lung-buster and only the llamas are really accustomed to life at this height.

In Vilavila, the schoolkids want to know all about our water filter. James cruelly plays on their innocence telling them that you put water in and get chocomilk out; they are crushed when they learn the boring truth!

As always, cake is never far from our minds. A long valley ride towards Lampa, reveals rock formations that clearly resemble the firm favourite and much-missed lemon drizzle (we’re blaming you for that, Lars!)

We reach the altiplano just before Lampa, and there’s nothing but straight lines and our own shadows to keep us company.

Small, pretty and friendly it’s not hard to choose Lampa over the nearby city of Juliaca as our base for arranging our Peruvian exit visa…

…and taking a closer look at the stunning church in the square, before setting off again towards Lake Titicaca and the Peruvian/Bolivian border.

Route notes

From Cusco, we took the pista south towards Juliaca, turning off just before Checacupe. We rode towards Acopia and onto a network of back roads to Lampa via Yanaoca, El Descanso, Hector Tejada (aka Pallapata), Jauni, Cacycho, Vilavila, Palca and then Lampa. It’s a mixture of paved and good dirt, with the main pass just before Vilavila. From there it’s onto the altiplano, and flat and fast to Lampa. Our total distance from Cusco to Lampa was 413km, and took us 5½ days riding.