Lake Titicaca – and Bolivia by the back door

October 1st, 2013

As we reshuffled our idea of descending into Arequipa’s canyons due to lack of time, our exit from Peru suddenly included visiting the famous Lake Titicaca. Sitting astride Peru’s and Bolivia’s border, the local joke goes something along the lines of “Peru got the titi and Bolivia got the caca” but our trip around the lake was equally enjoyable on both sides.

There is no immigration control on the far side of the lake, so from Lampa, we travelled by bus to get our passports stamped in Puno (more details at the end of this post) before visiting the Capachica peninsula and then riding the eastern side of the lake on quieter roads to the border at Tilali.

Sarah & James

Our “high tech” map of the Capachica Peninsula (with our route marked in pink) which reaches out into the lake just to the east of Juliaca. We spend a few days here before heading towards Bolivia…

…but to get there, first we have to ride past this. Stretching out of Juliaca on the windswept altiplano is 15-20km of rubbish. Some brave souls sift through it for treasures to keep and sell but mostly it’s broken tvs and used nappies.

After riding through the town of Capachica, we reach a gate shaped as the hat typical to this region and we know we have arrived at the lake…

A rest day is prescribed and we pitch the tent at Kawai homestay near Llachón, overlooking the lake and back towards Puno…

Kawai homestay: Magno and his family provide accomodation and tasty local meals overlooking the lake, just outside of the village of Llachón.

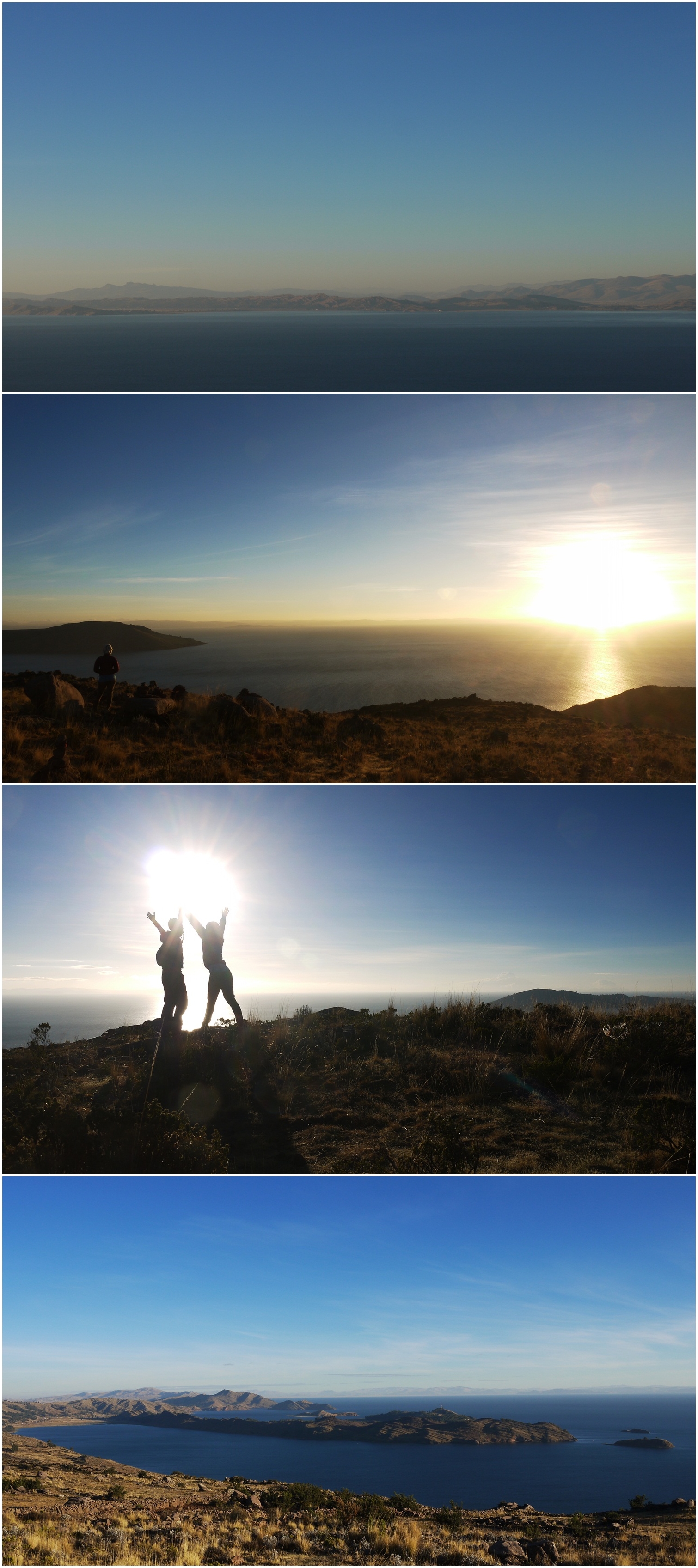

We drag ourselves out of the tent at 0430 and up to the highest point of the peninsula to see the sun rise over the lake. The magnificent views are more than enough reward for the effort – thanks for the tip Alfie!

And we still make it back to the homestay in time for delicious fresh doughnuts and jam for breakfast.

A leisurely ride around the rest of the peninsula and we are at Playa Chifrón just in time for lunch on the beach…

Riding away from the peninsula towards Escallani, we follow a wonderful dirt road that hugs the coastline…

…and the boats are out collecting totora; the prolific reed that grows on the shore is used for everything from eating to weaving to animal fodder.

The people of Huancané, upset with their corrupt mayor, lay a road block in protest. Thankfully cyclists are allowed through…

…and we reach the “other” side of the lake. Little traffic and beautiful views make it the perfect way to leave Peru.

…nothing for it but to get stuck in. It freezes my brain! I am really not a fan of jumping into cold water but I can’t just sit on the beach and observe; this is Lake Titicaca after all.

We warm back up in the sun and enjoy sweet granadillas; this kind of tropical fruit will be harder to come by in Bolivia, we are told, so we eat as much as we can in our last few days in Peru.

After passing the police checkpoint at Tilali, Peru has one tough climb left for us. I grumble all the way up and vow to make a case to the Office of International Border Crossings (there must be one, right?) that they do not always have to choose difficult dirt climbs to mark the territories between countries…or perhaps it’s just the particular borders we choose to cross at?

There’s no one else up here, just hundreds of empty buildings that are used on Wednesdays and Saturdays for a huge contraband market.

No-man’s land (and the climbing) continues much further than I anticipate; it’s an 18km slog from Tilali to Puerto Acosta, the first town on the Bolivian side. We arrive shattered and seek out dinner…

…which we find at a kiosko in a deserted square. First food impressions are positive: hot hearty soup followed by a heaped plate of rice, potatoes and minced beef for just over US$1. Exactly what is needed.

Our first impressions of Puerto Acosta on the otherhand are pretty bleak – we arrive as it’s getting dark and there is a bitter wind blowing around a town where seemingly no one lives. The following morning both the people and the sun emerge and it’s a much nicer place to be.

And our first impressions of bananas – the crucial staple food of cyclists – they’re cheap, really cheap. In Escoma, 4 bananas costs us 1 Boliviano…in sterling, that’s 44 bananas for £1!

We continue to follow the lake on the Bolivian side, through peaceful villages where running is a rarity…

…on to Ancoraimes, now truly on the altiplano, where bicycles are the most common form of transport. We get swallowed up in the school commute.

Ché propoganda reappears reminding us of our month in Cuba, nearly two years ago. His final guerilla campaign took place in Bolivia before he was captured and shot by the Bolivian army and CIA at Villagrande; his iconic face can be found everywhere here.

…and encounter more locals who opt for cycle transport. This cholita with trademark bowler hat balanced precariously and pleated skirt flowing, does her shopping by bike.

We make it to El Alto (the city above La Paz) in no time, practically free-wheeling along the pancake-flat altiplano. At the border between El Alto and La Paz known as La Ceja (“The Eyebrow”) we are treated to an unforgettable first view of the city with the snow capped peak of Illimani in the background. Time for a few days off to gather ourselves before we head back out onto the altiplano…

Route notes:

We followed the excellent information on Bicycle Nomad and from Harriet and Neil on the Andes by Bike blogs – here are a few additions and updates:

Lampa (35km NW of Juliaca on the secondary routes to and from Cusco) is undoubtedly a more pleasant base than Juliaca for the immigration trip to Puno. It’s 1½ hours each way in combi from Lampa – Puno with a change in Juliaca.

Peruvian immigration:

In Puno we were given our Peru exit stamp dated for that day. According to the immigration agreements between Peru and Bolivia, we were then told that we had to present ourselves to Bolivian immigration within 7 days. This was plenty of time to get to Puerto Acosta, even with our Capachica Peninsula detour.

Capachica Peninsula:

To access Capachica, ask in Juliaca for the road to Coata. The most spectacular section of the loop was the cliff-top ride from Chillora to Escallani on the eastern side, en-route to the main Juliaca-Huancané road at Taraco.

To take the coastal road from Moho (highly recommended), ask for the paved road to Tilani via Conima (38km total Moho-Tilali). Leaving Tilali, you pass through a final police checkpoint, and then climb up to the border line by the smugglers’ market. From here it’s a rough climb and descent into P.Acosta (18km total Tilali-P.Acosta).

Bolivian Immigration:

We were given a 30 day tourist visa in P.Acosta. We tried to get this extended to 90 days (apparently this is easy at more major crossings), but were told we had to go to La Paz to do this – which we did, free of charge and with no hassle.

Our total distance from Lampa-La Paz was 502km (it would have been 386km without the Capachica detour), and took us 6 days riding.

A Chilean interlude

October 31st, 2013

Joined by our friend Anna – who we have repeatedly bumped into over the last year but had never quite managed to cycle with so far – we set off together from La Paz. The aim was to leave Bolivia briefly and enter Chile, hunting for volcanoes, salars and thermal baths through the Vicuñas and Isluga national parks .

Two weeks of riding in little-visited corners of Bolivia and Chile covered a wide spectrum of physical discomforts and absolute pleasures. Scraped, chafed, burned, steamed, scratched, sore, parched, blistered, windswept – and yet at the same time mud-bathed, elated, relaxed and awed; we enjoyed every minute of cycling in this remote and epic landscape.

Sarah

The ‘overflow’ Casa de Ciclistas in La Paz is at Mabel’s house; Mabel, stepmother to indefatigable casa host Cristian, also hosts cyclists in her very comfortable basement. We are received as family and really hope to see Mabel, Pablo and Yolita again.

Before leaving, we are lucky to spend time with some very hairy Alaskans. Max, Kanaan and Andy of “A Trip South” introduce us to Russian dumplings, excessive egg eating and the finer points of taming facial hair that is over a year old.

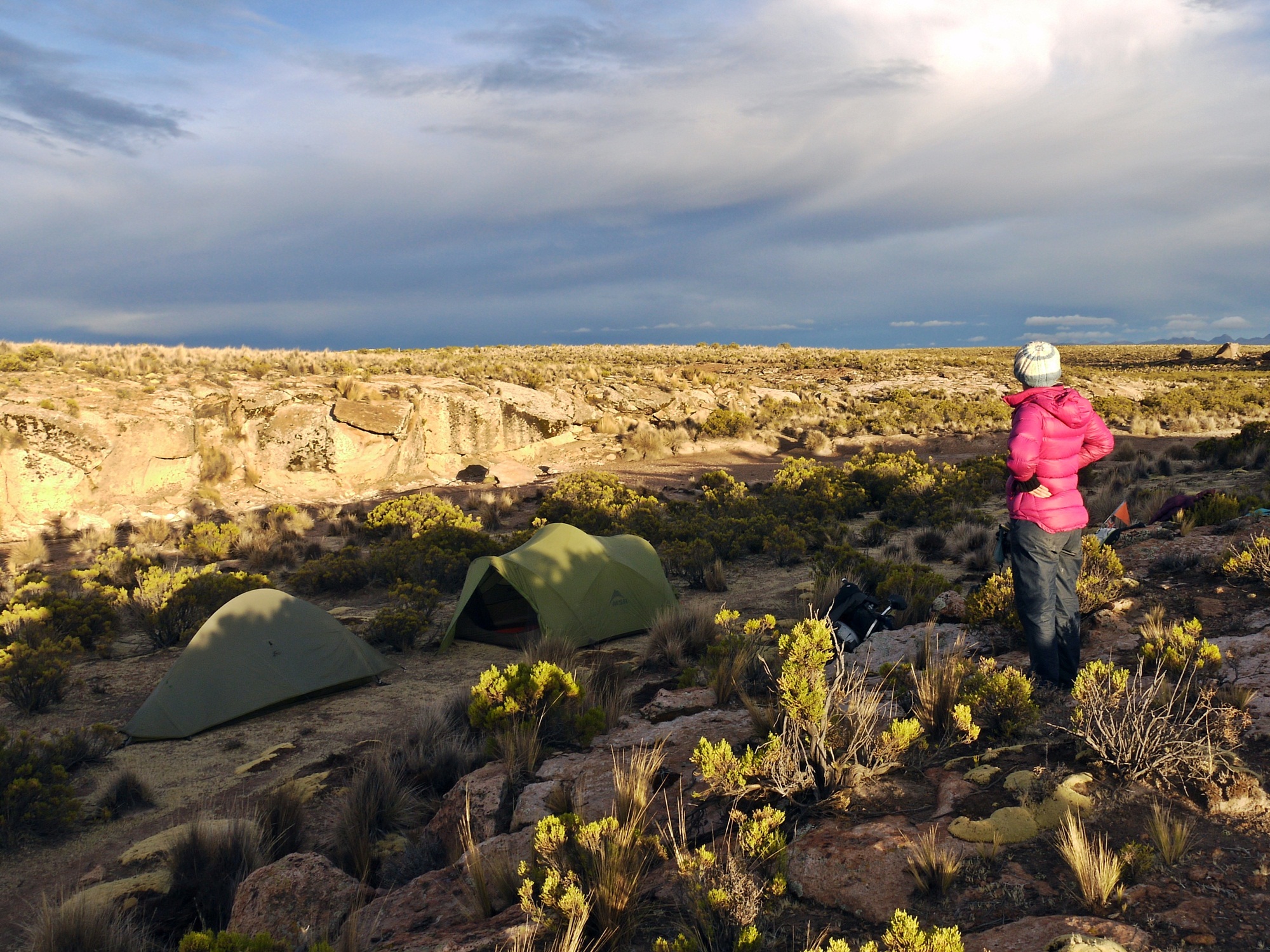

After the frantic road out of La Paz, we welcome the solitude that the desert brings on the second day.

Wild camping with Anna, we begin cooking together. Travelling with other cyclists obviously requires a certain amount of adapting to each others’ ways. We soon find though that on the most important topic (food) Anna’s appetite and hunger for good camp food matches ours and a beautiful new cooking team is born.

Just one of an eclectic mix of tasteful posters we get to peruse while having lunch in a shop in Curahuara.

An icy downpour forces us off the road and into a disused shelter. The stove comes out and in a flash we are huddled over cups of tea until the weather clears…

No photos please! Anna gets ‘papped’ with her own camera in the hands of Maria Luz, one of the residents of Sajama with a keen eye for photography.

There’s not much going on in Sajama, and the handful of village shops are rarely open. We patiently knock, and wait, and hope…

…supplies are short and we have to improvise but there’s still sufficient food to throw three cyclists into a cooking frenzy back in our hotel room…

We are forbidden from carrying fruit, vegetables, dairy or meat into Chile and not expecting to encounter shops or restaurants on the Chilean side, we have prepared reluctantly for a five day stint of dried foods and basic meals. We strike gold however on the first morning – a roadside café offering delicious fried egg sandwiches…

We share the road with a procession of trucks on their way to Arica on the Chilean coast. Despite being very courteous, the lorry drivers can’t avoid covering us in layer after layer of dust.

…and finding ourselves on a wide empty plateau in the early evening, we have to push 3km through sand and wind to find some shelter for camping.

After a silent night of tranquil camping, we are just a short hop away from the edge of Chile’s Salar de Surire. A wide, bright, sparkling, deserted expanse of salt and a haven for vicuña and flamingos.

…contrast with the dazzling white salt and turquoise thermal pools. We arrive at the thermal waters at Polloquere…

…and jump in. James quickly returns to his “creature from the deep” incarnation, last seen on Lake Tititaca…

…and I scoop up the silky mud for a face pack. In the cold afternoon winds, the warm waters at around 45°C are bliss…

… but it’s a very different story out of the water. Getting straight into warm clothes is a race as the temperatures plummet. We layer up to keep warm…

Dragging ourselves away from a luxurious morning of mud wallowing, we begin our journey back towards the Bolivian border. With barely anything marked on our map and only having seen a handful of lorry drivers for days, we are surprised to find so many place names marked on this road sign…

Crossing back into Bolivia is quick and easy and soon we are back amongst the truckers as the sun sets over the border town of Pisiga.

Keen to camp, we accept an invitation from friendly Miguel (who owns the local grocery shop in town) to camp with his baby llamas. They insist on overseeing every aspect of our routine, and welcome us appropriately back to Bolivia.

Anna also blogged about this section of our trip and you can read it here.

Route notes:

Bolivia:

Route: La Paz – Patacamaya – Sajama – Tambo Quemado

– Reached Sajama via unpaved back road which loops to north of Volcán Sajama via Ojsani and Tomarapi – recommended. Turn off level with telecom towers on hill, towards rock forest.

– Last shopping opportunity in Tambo Quemado on Bolivian side – we didn’t see a shop again until we crossed back into Bolivia at Pisiga, 5 days later.

– No fresh fruit, veg, meat or dairy products into Chile – they scan your bags to check. Peanut butter OK, honey and jam not!

Chile:

Route: Guallatire – Chilcaya – Enquelga – Isluga – Colchane

– From customs and immigration, back track a few hundred metres and take the turn on the bend signed to Guallatire – an unpaved, sandy road which climbs to a pass. 10km from customs to Chirigualla hot springs – we slept cosily inside the hut.

– Polloquere hot springs – approx 32km from Chilcaya. Follow dirt road around the east side of the Salar de Surire. At junction in corner of salar, keep right (left turn, uphill, goes back to Bolivia) – springs are on right after a couple of km.

– After springs, continue on this road to a well-signed junction – turn left towards Colchane.

– Food: roadside comedor 10km before Guallatire – also sells biscuits. Other than that, we saw no shops in Chile.

– Water: never carried more than a day’s supply – available from Customs post at border, carabinieri (police) at Guallatire and Chilcaya, and some freshwater springs on the pampa after the Cerro Capitán pass.

See our map for a route overview.

Cycling on a sea of salt

November 5th, 2013

Ask a cyclist at the start of their trip what they are expecting from it, and they will probably be able to reel off a list of highlights to you – a mental collage of images, anecdotes and place names gathered from months of preparation reading cycling blogs, gazing at photos and scouring maps. Every classic cycle touring route has its iconic rides, and for anyone riding through South America then a crossing of the Bolivian salares (salt flats) is probably near the top of the list.

Of course, it’s usually a recipe for disappointment. By their nature, the most hyped rides are often just that: over-hyped. Chances are it will be the hidden gems, the rides that take you by surprise when you are expecting nothing that you will still be talking about years later. Certainly that has been our experience so far.

The salares, however, are – for us at least – a definite exception to this rule. Over the past two years we have crawled up a lot of beautiful passes. We have freewheeled down many stunning descents. We have seen amazing forests and rushing rivers. But so far we hadn’t yet cycled 120km across a crust of perfect, crystalised salt – and I’m pretty sure we won’t again. In a world where every competing attraction claims to be “unique”, the salares truly are something special – and the excitement of pedalling across them is hard to match, no matter how many photos you have seen before hand.

By way of introduction, the Bolivian salt flats were formed by the drying of a giant prehistoric lake, called Lake Minchin. As the lake dried, it left behind several salares, including the Salar de Uyuni – the world’s largest salt flat, covering an incredible 10,500km². The salar is covered by a crust of salt up to several metres thick, but far more valuable is the brine underneath, which is rich in lithium. The Salar de Uyuni alone is estimated to contain up to 70% of the world’s lithium reserves – that’s a lot of batteries. In keeping with Bolivia’s current policies against foreign exploitation of its natural resources, there is currently no mining on the salar. There are however plans to create a Bolivian-owned and operated pilot plant to begin lithium extraction – who knows what effects this will have on this fragile environment.

After a Chilean salar aperitif around the Salar de Surire, our Bolivian salar starter took us across the Salar de Coipasa, before moving on to the main course – a ride across its bigger and more famous brother, the Salar de Uyuni. Each of the three salares had their own character: the wildlife and hot springs of Surire; the complete solitude of Coipasa; and the sheer enormity of Uyuni.

James

Our route from Pisiga/Colchane on the Bolivian/Chilean border takes us first onto the Salar de Coipasa, through the Sierra Inter-Salar to Llica, and then diagonally across the Salar de Uyuni to Colchani.

Waving goodbye to our young llama hosts in Pisiga, we stock up on food and water – after five days in Chile without seeing a single shop, we are learning fast that when you see food around here, you make the most of it. We head towards the Salar de Coipasa, through typically deserted altiplano hamlets populated by sleeping dogs and rusty cars.

On the way, we remember to pick up that all important tool for salar camping: a rock. Without that, we have no chance of getting our tent pegs into the hard salt.

The sun here is ferocious, not just from above but also reflecting back up at you from the salt below. We hear stories of cyclists who’d ventured out onto the salt without sunglasses and ended up snow-blind for several days. Taking no chances, Anna gets into salt ninja mode using one of her custom-made buffs.

The salt at the edge of the salar is thin, cracked and soft. We work our way across it, the salt crackling under our tyres like fresh snow.

In places the cracked salt has formed raised, hollow pyramids and we invent a new game: salt breaking. It’s great fun – until of course I get slightly carried away. Apparently thinking I’m aboard one of the 18 wheelers from Ice Road Truckers instead of a fairly delicate touring bike…

…I take on a slab that’s a bit too big to handle. Instead of crashing through the salt as expected, the bike stops dead, I am launched into the air…

…and the front end of my bike shunts backwards, leaving me with a front fork that is far more banana-shaped than its previously elegant curve. Amazingly, the bike is still rideable – just with slightly dubious steering and a new toe overlap. Rule #1 of salar riding: salt is tougher than you think.

…and then, finally, we’re onto the good stuff: smooth, hard-packed salt. With the wind picking up, we decide to postpone our salt camp, and head instead for Coipasa island…

…where we find a sheltered camp spot with a breathtaking view over the flats. After a few days of spluttering on dirty Bolivian fuel, our fancy new Primus stove finally packs up. Thankfully, Anna’s trusty Trangia alcohol burner is at hand to cook up a delicious soup. We pack the Primus away and resolve to make ourselves a DIY alcohol stove to see us through the rest of Bolivia. All in all, not a good day on the kit front.

The first 20km the next morning are spectacular: hard, fast and without a breath of wind. We fly across the salar, before we reach a decision point: the jeep tracks veer east, whereas we want to continue south. We push on south, confident that we can find a “shortcut” to shore.

Rule #2 of salar riding: there are no shortcuts. The salt becomes thinner and more sponge-like; a salty slush that sucks at our tyres and drains our legs within minutes. If the first half of our morning is like riding on perfect new asphalt, then the second half is like riding through treacle. We push a long, slow 18km to shore, finally falling into the shade of an abandoned village square for lunch.

It’s not the end of our pushing for the day either. The “road” that leads to Llica is a typically Bolivian cocktail of dirt, washboard and sand. Most of the time you can pick a rideable line through it…

…but sometimes, there is no avoiding the sandpit. Our puny, long-neglected upper bodies get their second workout for the day…

…and we finally roll into Llica – where most of the village is busily engaged at the cemetery, getting very drunk to celebrate el dia de los muertos (Day of the Dead). We find ourselves double plates of roast chicken, before collapsing into a cheap hospedaje for our first shower in 10 days, and a long, well-deserved sleep in a bed.

First priority the next morning is a scrub down of our salt-encrusted bikes to try and keep the rust at bay, followed by a re-supply of the all-important chocolate stash.

Then we’re onto the big one – the Salar de Uyuni: an endless expanse of perfectly flat salt, and very little else. This time we stick to the jeep tracks, and the surface is a dream: hard-packed and fast…

We team up with Jan and Eva – two Slovakian cyclists we met in Llica – for our first night’s camping on the salt. Out comes the trusty rock, and with no shelter on offer we batten down all the hatches.

…and revel in the blissful solitude. No dogs, no TVs and no car alarms. Just us, the salt, the stars and perfect silence.

The next morning, we are up at 4.30am and pack quickly for the chance of a sunrise ride across the salar. Leaving Jan and Eva sensibly tucked up in their sleeping bags…

We head for Isla del Pescado, one of several islands which are the remains of ancient volcanoes submerged when Lake Minchin was formed.

With stomachs rumbling, we rustle ourselves up a picnic table from blocks of salt and enjoy a leisurely breakfast.

It’s a beautiful, yet surreal place – the enormous expanse of white still keeps tricking my mind into thinking I’m sat on the polar ice cap, surrounded by an alien invasion of enormous cacti from the tropics.

Rule #3 of salar riding: the perspective shot. We pay tribute to the two things that have kept these three cyclists’ legs turning over the past two weeks. Firstly, the humble Sublime – at 175 calories of chocolate and nut goodness for just 32g, a cyclists’ dream. We gave up messing around and buying them individually a while back – now we bulk buy in boxes of 24. Sadly, we’re yet to find one of these super-size versions…

Secondly, the stove-top cafetera – probably our most prized piece of kit (and also possibly the main reason why Anna stoically put up with our faffing and general slowness for the past two weeks). If only it was this big – imagine how fast we’d go…

After a relaxed morning on Pescado, we head towards the salar’s more famous island, Incahuasi, which floats in the distance through the heat haze.

After 24 hours without seeing another person, it’s a shock to come across this mass of 4x4s and day-trippers. Luckily though, we find what we are looking for – a tap, meaning we can fill our water bags for a second night on the salt.

Paved roads are hard to find in Bolivia – and so in the dry season the salar becomes a main transport route across the altiplano.

We pause at a hole to investigate what lies beneath. The crust of the salar varies in depth from tens of cms up to several metres, and floats on a sea of muddy brine. Continuing my polar theme, I was still half-hoping to see eskimos sitting fishing around these holes in the “ice”.

How to pick a spot when you’re surrounded by 10,500km² of camping perfection? Just close your eyes, keep pedalling, and stop when the urge takes you…

…and settle in for a second night of probably the easiest wild camping we will do on the whole trip.

Finally, we bid our trusty rock farewell (left in case of a fellow camper in need), and head for shore – a bumpy last leg along well-travelled jeep tracks.

Colchani, at the salar’s eastern edge, is the base for salt extraction. I was expecting a large-scale, commercial operation – but instead it’s endearingly Bolivian: an old guy with a spade, his bike leaned nearby…

From Colchani, it’s a short final hop to the Wild West railway town of Uyuni: a blend of tour agencies, pizza restaurants and rusting trains…

…all presided over by the usual collection of amused, flat-capped old men in the square. We settle in for a few days of serious eating, resting and stove construction – with the added bonus of a pizza-fuelled catch up with Neil and Harriet, friends from Huaraz who arrive fresh from their trail-blazing “Great Divide” crossing of Peru.