Canyons and climbs: into Peru

June 17th, 2013

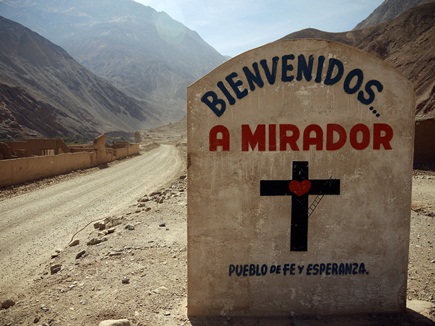

Welcome to Peru

Epic. It’s an adjective often over-used, but it looks like we might be using it rather a lot in Peru. For once, the hyperbole seems appropriate.

Our first impressions are of a country in which everything is on a grander scale than we’ve experienced so far: deep river gorges rushing their way towards the Amazon, never-ending climbs that inch up into the Cordillera Central of the Andes, spiraling descents which plunge us back down into the heat of the valleys, and mountain hospitality on a scale we haven’t experienced since Colombia.

Here are some snapshots from our first few weeks in this vibrant country of contrasts, from the sweaty border crossing at La Balsa to the bustling city of Cajamarca in the northern highlands.

James

New backdrops: through the last of the mud and roadworks, and into the coffee plantations of San Ignacio.

A gentle introduction through the rice paddies…

…and a first crossing of the Río Marañon at Bellavista.

Scorched desert and big skies on the way to Bagua remind us of Baja California, Mexico…

…and a roadside cactus has me dreaming of sponge cake for days to come.

We ride into the gorge of the Río Utcubamba…

…where we stop in the shadows and stare…

…before emerging into the sunlight, speck-like against the towering canyon walls.

Just as we almost forget we are in the Andes, the climbs begin. Contrary to what this sign suggests, where Ecuador goes for direct and brutal, Peru goes for long and gradual…

…up out of Leymebamba into the wind and driving rain, leaving us shivering and seeking shelter and hot drinks at the top.

But as we crest the pass, it all becomes worthwhile – we gawp, awestruck, as the descent to the river opens up before us.

Down we go – from 3,700m at the top…

…past the crinkled slopes in the evening light…

…60km of exhilarating switchbacks which replace earlier tears with grins…

…until we emerge at the bridge, almost 3 vertical kilometres below where we started.

From here there is only one option. Up we grind again…

…an all day climb, following a spaghetti-like thread across the mountain…

…and along precipitous ledges. These, finally, are the Andean roads that I’ve been daydreaming about for years.

New friends: “Griiiiingo!” they shout…

…but stop to talk, and we find real warmth. Polín stops us halfway up a climb and plies us with beer all night to celebrate our 20,000km…

…before sending us on our way the next day with a breakfast of fish and yucca – and our worst hangover for many months.

In Bagua Grande, our request to the Police Chief to camp in his yard is turned down – instead he phones a friend…

…and we find ourselves with a police escort to a complimentary night at the local love motel – complete with heart-shaped bed and jacuzzi. We decline the room service menu (catering to all your needs, from roast guinea pig to the morning after pill), and fire up the petrol stove for some spaghetti – probably a first for this room.

I stop to admire a vintage bike with a prancing stallion…

…and Celestino invites us in. He notes down our names, ages and nationality, before showing us a lifetime’s collection of random belongings…

…another bike restoration in progress resting on a stand of two coffins, an impressive range of buckets…

…and outside, even more bikes in the queue. Before we leave, he explains that he is old, with no family, and perhaps he could leave the house and his belongings to us…humbled, we graciously decline.

Some friends pop up in the most unlikely of places and demand to play…

…while others provide simple respite for weary legs. In Palmira, 92 year old Misael offers us a seat to eat our lunch – carved from a palm which he himself had planted 25 years earlier, and which gave the town its name.

Glimpses into the past: a chance meeting sends us to the home of Línder in Chachapoyas. The flags are out in his barrio of Higos Urco…

…to celebrate the anniversary of a victorious Chachapoyan battle against the Spaniards in Peru’s fight for independence.

We arrive in time to take part in the morning ceremony…

…attended by the city’s great and good…

…but struggle a little at 7am with the celebratory cow’s hoof soup…

…despite being served up with great charm by the local matriarchs.

A day’s detour on foot sends us on a steep climb into the clouds…

…in search of the ancient hill-top fortress of Kuélap…

with the help of a new friend, who we christen John – until we discover that John is a she. Juana, perhaps.

The perfect spot from which to spy your enemy below…

…before they even get near the impenetrable walls.

Now reclaimed by nature…

…and colonized by a new army of invaders…

…a perfect playground just waiting to be explored.

In Leymebamba, perfectly preserved history of a different kind: an incredible collection of mummies discovered at nearby Laguna de los Condores.

A new country, maybe, but some things never change: the rest day challenge – squeezing ourselves and our bikes into ever-smaller hotel rooms for a frenzy of cooking, cleaning, repairing and communicating…

….the constant calorie hunt: a lunchtime snack of homemade guacamole and fried plantain to stock up the fat stores…

…and liquid refreshment in both natural forms…

…and slightly more artificial. The luminous drink line up has been expanded with a new kid on the block: the fluorescent yellow Inca Kola – so sweet you can feel your teeth loosening as you drink it. So far I’m resisting, but if these climbs continue…

Two wheels; different ways

July 1st, 2013

Having been cycle-touring for a while now, I realise that although I find every day a challenge in one way or another, it barely scratches the surface in comparison to the feats of other cyclists.

For example: the couple who completed the 2500 mile Great Divide Mountain Bike route in the US on a unicycle; the family who left home for a true Latin American adventure together; the Spaniard who has been riding his bike around the world for the last seven and a half years; the Australian who always, always finds the back road alternative no matter how hard; the French couple who do it by tandem, or the Canary Islanders who gave up backpacking, built their own touring bikes out of recycled parts, adopted a puppy, strapped her to the front of the bike and set off for the mountains.

We have met all of the above cyclists on our trip (except for the unicyclists who I would just love to share a beer with) and more, who continue to inspire us, challenge us and show us that there are so many different facets to bicycle touring.

For my part, after two years I simply continue to enjoy the ride, to be amazed at new landscapes, continue to love meeting new people – cyclists and locals. If we can follow just some of the tyre tracks of those who inspire us, and absorb some of that incredible energy, we’ll have enough steam to get us to Patagonia.

The latest leg of our trip was not lacking in inspirational landscapes or people and as the road brought us nearer to the mythical Cordillera Blanca, the thrill of the ride never waned.

Sarah

By lunchtime, we are admiring the condor statues at Condormarca – unfortunately none of the real birds make an appearance.

Into the rural fields outside of Cajabama and James gets a whirlwind intro to tile making; moulded out of earth, sand and water…

A classic Latin American view as we pass through the regrettably named Shitabamba: maize kernels drying on sheets in the sun and political campaigning painted directly onto the walls of houses.

We unload the bikes at Huamachuco and make the 10km rocky climb up to the pre-Inca ruins at Marcahuamachuco…

More than once on this section we are scratching our heads about which of the identical unsigned tracks to take…

After 21,000km another rocky descent is one too many for my front tyre. Not bad for two years of rough riding. So we swap a Marathon Extreme (now discontinued) for a Marathon Mondial – initial impressions are that it doesn’t seem to offer as much grip, but we’ll see how it goes.

…brings us to the dairy at La Victoria near Cachicadán. A beautiful camp spot and chatting with lively local dairyherder Marléne (on the right) is the perfect way to end the day.

The following morning, we can’t leave without buying some of the produce; the kids wave us on our way…

…but it’s not long before I insist on stopping to sample some of our purchases: manjar, spreadable fudge, on fresh crusty bread. Yum.

Lunch feels practically European. Unexpectedly, we have been able to get hold of Swiss-style cheese, meaty olives, juicy tomatoes, creamy avocados and fresh bread. More yum.

The afternoon delivers a nasty punch with a challenging river crossing on a bridge that looks about four hundred years old, a scramble over rocky roadworks and then a gruelling climb up to Tulpo.

…only to be confronted by the afternoon’s challenge. Twenty four hairpin bends and a 20km climb to Pallasca…

…where, when we arrive, the most pressing job as always, is to seek out calories. Sometimes we hit the jackpot – this fritter is the perfect quick fix…

…and sometimes there are bitter failures; what appears to be tasty looking cake is filled with a foul excuse for jam, rendering it nearly inedible.

We make sure to visit the bread lady before leaving Pallasca not knowing where we’ll end the day – but certain that…

…there’s a big downhill in store. 25km of descending into the Rio Chuquicara gorge and then it’s all flat riding or downhill.

Sure enough, exactly 10km later we are sheltering from the wind in a palapa at Chuquicara. A morning stretch is needed before we set off towards Caraz through the Cañon del Pato.

…when James is joined by a companion on a bike. Segundo, a local security guard who patrols this stretch of road on his two wheels, tells us there are two other touring cyclists just ahead.

They are Spaniards Kalima and Charco, riding up into the mountains on handbuilt bikes from the coast, with their new puppy “Cicla” (rescued from a rubbish dump in Trujillo) stowed away in a box on the handlebars.

…before they teach us a thing or two about taking roadside breaks the next day. Charco has a blender attachment on his bike and they soon knock up four papaya smoothies…

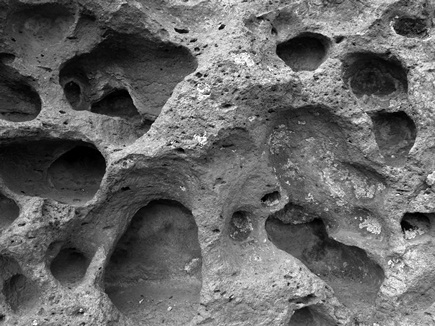

The final stretch to Caraz is through the famed Cañon del Pato, a series of thirty six tunnels cut into the rock where the passage between two mountain ranges is more than a tight squeeze…

Breathing in for the cars and buses which come screeching through is not an option; stopping is mandatory.

Last stop on this leg: Caraz and the gateway to the Cordillera Blanca. From the town square the stunning peak of Alpamayo is cutely juxtaposed with swaying palms. Snowy mountain adventures await us…

La Cordillera Blanca: a tale of two passes

July 14th, 2013

It felt like this ride had been a long time coming. Ever since we decided to sit still in Colombia and wait out the worst of the Andean rainy season back in September last year, we’ve had half an eye on Peru – and in particular on giving ourselves the best chance of riding amongst these snow-capped peaks in all their glory.

For mountain lovers, I can’t imagine it really gets much better than the Cordillera Blanca. Outside of the Himalayas, this is the highest mountain range in the world, with 22 peaks over 6,000m squeezed into an area just 21km wide and 180km long. This makes for mountains that are incredibly accessible, yet still surprisingly unspoiled by the crowds; just a few hours walking or pedalling from the valley, and you can be standing at the foot of a glacier or beside a turquoise Alpine lake – probably with no more than a stray llama or mule for company.

As always, the most difficult part was deciding how to squeeze as much as possible out of our limited time here – the age old bike touring conundrum of must-see sights vs progress vs budget vs I’m knackered, let’s just sit around, drink coffee and eat cake. Consoling ourselves with the rapid realisation that this was likely to be the first of many visits here, we opted for a five day loop by bike which we hoped would give us just a taste of what these mountains had to offer.

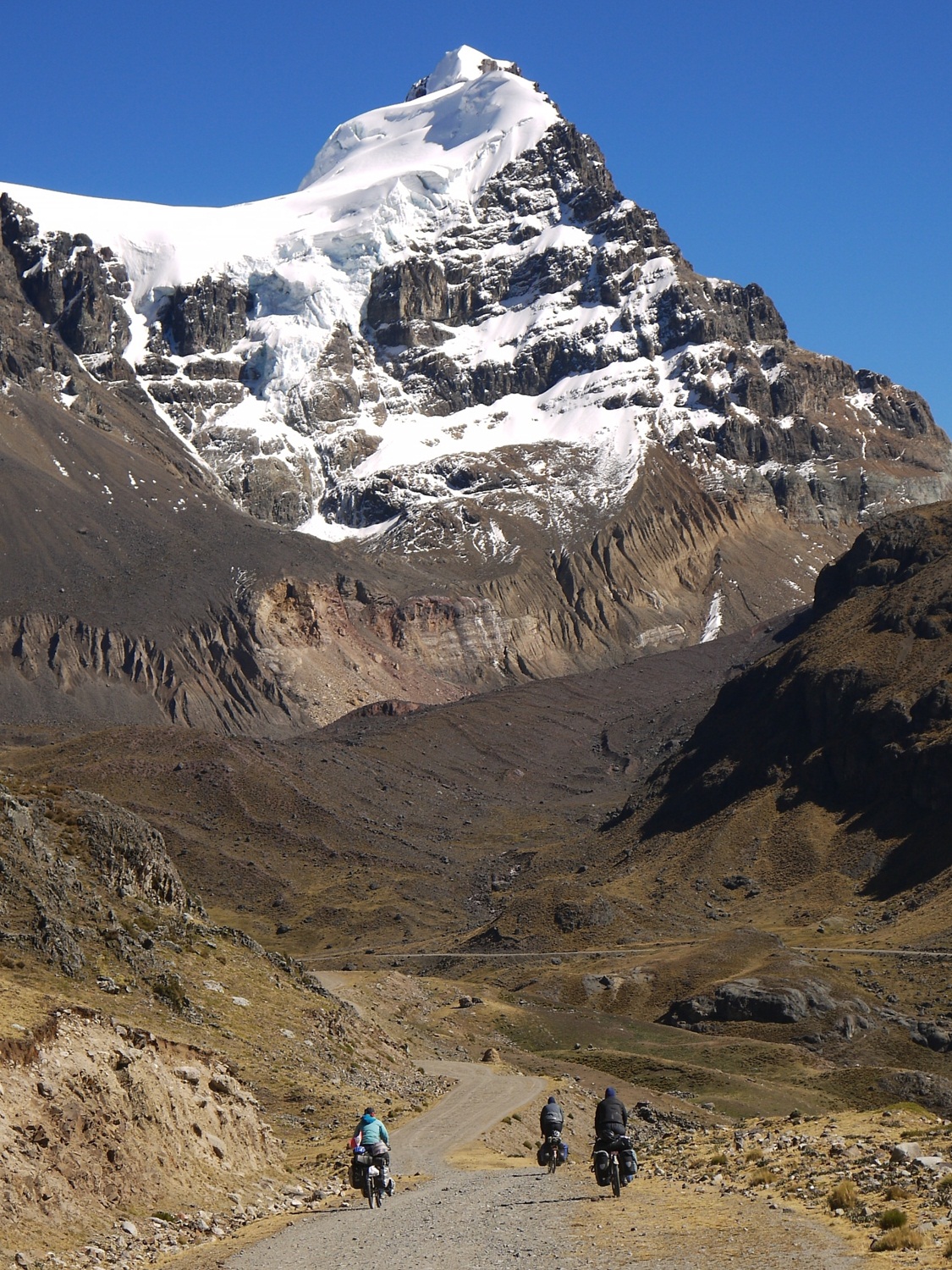

And so, with the help of some wise words from our cycling godfather Salva (who we’d first met in Panama, near-missed through Ecuador and finally seen again in Caraz), we plotted a route which would take us from Huaraz across to the eastern side of the Cordillera and back. On the way, we would take in two of the four passes which cross the range at an altitude of just under 5,000m: Punta Olímpica and Portachuelo de Llanganuco. It would, we figured, be a fun test of legs, lungs and sleeping bags – with some glaciers and lakes along the way just to distract us from the lactic acid and hyperventilation.

So after an overnight warm-up ride to Laguna Parón from Caraz, we were ready. All that was missing now was that clear blue sky we’d spent the last 10 months waiting for…

James

A false start: we make it along the valley to Carhuaz before the clouds roll in and the peaks disappear. We cut our losses and find a hostel. The next day is even worse – we load calories and try to curb our natural impatience. Finally, on the third day, we wake to clear skies…

The bikes: with excess baggage stashed in Huaraz, for us this is “fast and light” mode. Or, more realistically with full camping kit and lots of warm clothes: “still slow but not quite so ridiculously heavy” mode.

From Carhuaz, we climb up the valley towards Shilla, a small village in the foothills of the Cordillera…

…where the immaculate square is occupied by the usual contingent of two snoozing old men and one sweeping lady…

…and the roadside is lined by the local pig population. Forget the dogs – a small pig would be my pet of choice for this trip. It’s a pragmatic choice: entertainment, waste disposal and – when it gets too big for the bar bag -bacon…mmm, bacon…

Ahead the Cordillera gets closer – here the mighty peak of Huascarán Sur, the highest in Peru at 6,768m…

…while the less dramatic peaks of the Cordillera Negra retreat behind.

We reach the flat pampa of Quebrada Ulta as the sun dips and the shadows climb the canyon walls…

…a perfect spot to pitch for the night, with just a few inquisitive cows and the cracking noises of the glaciers high above us for company.

A cold night leaves a dusting of frost…

…and us shivering as we cradle our breakfast porridge and coffee. Finally, the sunlight begins to touch the surrounding peaks.

From the pampa, the switchbacks begin, and we work our way up. Salva, starting half a day behind, catches us…

…”The best pass in the world!” he shouts triumphantly – and after seven and a half years cycling around the globe, he should know.

We pass the new tunnel, swapping perfect asphalt for a final few kilometres of dirt towards the pass. Breathing turns into panting…

…as we reach the snowline and the glaciers close in around us…

…and then we’re there! Punta Olímpica – the high point of our trip so far at 4,890m. And what would any self respecting, serious cycle tourist do to celebrate – build a snowman, of course…

A quick stop for a bread and boiled egg lunch beside a beautiful lake…

…and we pile on the layers for the descent. A thumbs up from Salva, and down we go…

…perfect pavement all the way to Chacas. It’s a picturesque, time-stood-still Andean village with an unusual grass square – perfect for defrosting and drying still-frozen tents, and for mid-afternoon siestas.

Chacas is also home to a renowned community of Italian Salesian missionaries, the Don Bosco. They work with locals to produce beautiful woodwork, and have also built a hospital which serves the whole valley. We ask to camp – and instead are treated to a bunk bed and three delicious meals – including the best pizza we’ve eaten in the last two years. Grazie mile amici!

Coming from the stubborn school of sickness denial, I had hoped that some mountain air might rid me of a lingering cough and cold. Sadly not – the next day I can’t even stay upright long enough to ride around the square. And so we wave goodbye to Salva, stock up on Nastiflu…

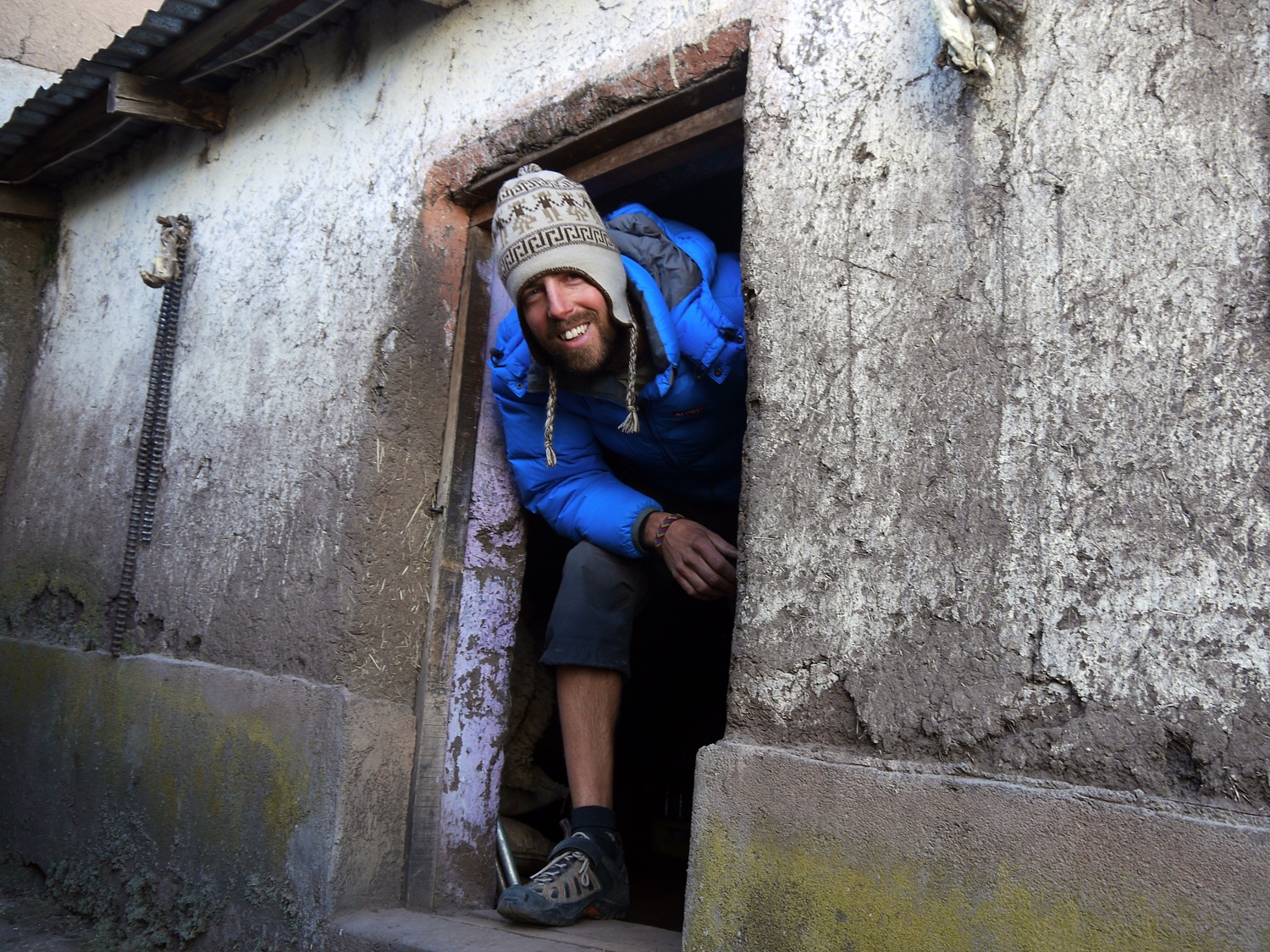

…and find ourselves a nearby hospedaje, where I retreat to bed. It’s our favourite kind of place to stay – miraculously held together by rickety pieces of wood, run by a friendly old lady who fusses around us…

…and full of family details like her husband’s beaten old sombrero…

…and a resident playmate for Sarah, with an in-built homing device for a warm sleeping bag.

The next day I’m feeling stronger, and so we head off along the Eastern side of the Cordillera, where drying maize is hung from every roof and balcony like Christmas decorations.

We coincide with afternoon rush hour leaving Sapchaa, and pick up an escort of schoolkids on their way home. They insist on running alongside and pushing my bike up the hills for the next 5km back to their village – if only they were on hand every day…

Soon we leave the dry and hot valley behind, and head back towards the snow caps once again. A late afternoon pass has us puffing…

…and then it’s downhill into Yanama, where we find a restaurant camp spot with a sunset view of the serrated ridges of the Cordillera.

Our luck with the weather continues as the next morning dawns clear. We make an early start from Yanama…

…a twisting 35km dirt climb up through the Quebrada Morococha, past stands of quenual trees with their burnt orange, flaky bark…

…and the delicate purples of Andean lupins.

The road becomes rockier and steeper – or maybe the altitude just begins to kick in – and we pass a series of beautiful lakes…

…then, in a flurry: a pair of foxes appear at the side of the road; our first Andean condor drifts effortlessly over our heads…

…a rock tunnel opens up before us and we crest the pass: Portachuelo de Llanganuco, 4,737m.

We take a breather…

…and take in the stunning panorama spread before us.

Down through the rocky hairpins we go…

…past Chacraraju (6,108m), commanding the valley like an impenetrable, icy fortress…

..until the Lagunas de Llanganuco lie in front of us .

We pick a stream-side camping spot for a spaghetti-fest and an early night.

The next morning the shadows slowly fall…

…and the sun casts its turquoise spell on Llanganuco.

A sobering moment as we pause at the monument to the hundreds of climbers who have been killed in the Cordillera Blanca…

All that remains is a jarring descent towards Yungay in the Callejón de Huaylas, toes and fingers defrosting as we pass Sunday league football in the shadow of Huascarán.

From Yungay, it’s a quick shuttle back to our comfy home-from-home in Huaraz, Santiago’s House. A hot shower and hot food awaits, along with the hypnotic view back along the Cordillera from the rooftop terrace. We’ve said “We’ll be back” about many places in this trip, but this time I think we really mean it. With some more time, a rucksack, tent, and a mountain bike, the possibilities really would be almost endless…

Rocks; very big rocks

July 31st, 2013

Whether it’s the towering peaks alongside the Pastoruri Pass outside of Huaraz or the mysterious standing stones of the Bosque de Piedras (Forest of Stones) near Cerro de Pasco, Central Peru has some impressive shows of rock.

I wouldn’t describe myself as a geology buff, but as we make we our way south through Peru, it has been impossible to ignore the swirls, textures, formations and sheer size of the Andes.

Sarah

We are about to take another pass over the Cordillera Blanca and ride through remote sections for three days, so we take on-board the emergency “bread blanket”…you can never have too much bread.

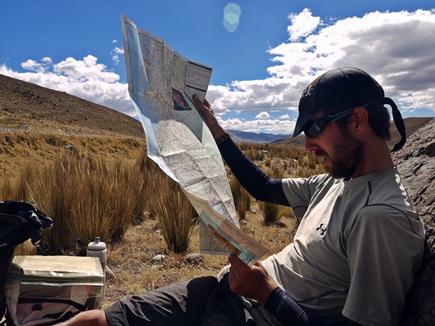

Only on the dirt road for a matter of minutes before we stop for lunch and James is found in his favourite resting pose: map gazing.

These incredible, enormous plants – also known as Queen of the Andes – only grow here and in Bolivia, between 3200 and 4800m.

…and keep climbing, where the craggy faces get craggier and the serious weather happens – it is snowing here.

…and another campsite where the curves of the ground are bathed in the last of the day’s golden sunlight.

It’s always a battle between enjoyment and endurance for me at this altitude: camping alongside jaw dropping landscapes is incredible…

…but you have to cope with seriously cold temperatures at nearly 5000m. The ice on our water bags freezes overnight inside in our tent…

…and, when we happen to ask, as always up in the mountains the hospitality is free flowing. We meet Lydia who quickly presents us with a bowl of the finished product: delicious cancha (toasted, salted corn) and two sweet mandarins to give us energy to finish the climb towards Huánuco.

On the way, I practice my Spanish/Quechua tongue-twisters trying to pronounce local village names – although this one looks Welsh to me.

Our back-road ride from Huánuco to Cerro de Pasco via Pallanchacra had its moments. Some very pretty…

…like stopping to admire llama’s pom poms (each farmer identifies their flock with different ear finery – tassels, pom poms, ribbons and bows)…

Others were downright nasty. At 4380m, Cerro de Pasco lays claim to being the “highest city in the world” and with a whacking great mine in the middle of it, it can also claim to be “one of the ugliest”…

…and “one of the coldest”. The only sensible way to warm up here: hot chocolate and a big slab of chocolate cake. James fulfills a long held desire in Cerro de Pasco: to buy an entire cake and eat it all. Mission accomplished.

We’re happy to leave Cerro de Pasco behind and explore the Bosque de Piedras at the nearby Santuario Nacional de Huayllay.

…and of course the most fun is identifying obvious formations that never quite made it into the official tour brochure.

At the end of our walk, in the mysterious “magnetic” stone circle, James puts into practice some of the meditation techniques taught at Rhiannon; although I could have sworn he was thinking about that chocolate cake again…

Lago de Junín: Escaping the Wacky Races

August 13th, 2013

If there’s one thing guaranteed to get a touring cyclist nervous (apart from a broken stove), then it’s a deadline. After all, deadlines are unwelcome memories from the “real” world; a long-forgotten past in which we didn’t have to regularly ask each other what day of the week it was. Flexibility and freedom are a touring cyclist’s mantras – deadlines are to be avoided at all costs.

But this time – much as we pretended otherwise – we really did have a deadline. Sarah’s brother Dave was coming to visit us in Cusco, and – as famously laid back as he is – we figured he probably wouldn’t appreciate spending half of his precious holiday waiting for us while we struggled over a last couple of Andean passes. Luck, however, wasn’t on our side. After being forced to stay longer than anticipated in Huaraz to rid ourselves of my cold and Sarah’s parasitic party, we found ourselves well behind schedule. No worries, we thought, we’ll stop being so precious and slip in a few main road sections (the dreaded, long-avoided “red roads” on our map) to make up some time – after all, how bad can they be?

Well, in Peru, pretty bad – as we quickly found out. If ever we needed a reminder of why we avoid these roads like the plague, then this was it. We’ve met some lovely people in Peru, but put the vast majority of Peruvians behind the wheel of a vehicle and they turn into neanderthals. Every country on the trip has had its share of bad drivers, but when it comes to being consistently atrocious, Peru really is in a class of its own. As a cyclist, riding a main road in Peru is like being thrown into a particularly surreal and lethal Latin American episode of Wacky Races – just without the funny bits.

The rules are simple. First, the use of brakes is strictly forbidden – instead just accelerate towards anything in your path, and if it doesn’t move, swerve around it at the last minute. Second, lean on your horn at all times like a four year old with Tourette’s – as long as you’re doing this, nothing will be your fault. Third, extra points are on offer for hitting anything in your way: old ladies, llamas, stray dogs, gringos on bikes – think of it as a slalom. And finally, at all times maintain an inane grin on your face, a mobile phone clasped to your ear and a piece of fried chicken in one hand.

Fortunately, after a couple of days spent swearing our way through near-death experiences, we realised that there was no way we were going to make it to Cusco in time anyway. For once, pragmatism won over our stubborn cyclists’ idealism, and we resigned ourselves to getting as far as we could before jumping on a bus for the final leg. Liberated from our deadline and so in turn from our paved road purgatory, we breathed a sigh of relief, and headed for the back roads once again.

And when we did, we were treated to one of our best day’s rides in Peru: a quiet dirt road hugging the western shore of the Lago de Junín, Peru’s largest lake sitting at just over 4,000m on the altiplano. In bad weather, this would be a bleak, desolate place – but in the sunshine, with a huge cobalt sky and cartoon-like clouds hung as if from puppeteers’ strings across the plain, it was just magical. After a day meandering along the lake, watching flamingos and absorbing the views, we found ourselves a beautiful lakeside camp spot: the perfect end to a great day on the bike, far from the Peruvian Wacky Races.

James

(Big panoramic photos don’t really work with our skinny blog, but you can open up a full-size version of any of the images by just clicking on them.)

Big Brother

August 30th, 2013

When you haven’t seen a close family member for two years, how will a two week visit pan out? Emotions building to a crescendo as we approached Cusco, I was experiencing anticipation, fear, dread, excitement and nerves at the prospect of my brother’s arrival in Cusco. What would we talk about, how would we entertain him, had he changed, had we changed?

It turned out that I had nothing to worry about and the sibling bond hadn’t evaporated – shared appreciations of food, drink, music and cycling meant that there were very few silent moments during his ten-day stay. With James and I having travelled in our own little bubble for so long, it was refreshing to talk to someone else about their adventures and plans. A lot has happened in Dave’s life over the last two years too and so it was great to catch up on his news and experiences, and lay off our repetitive subjects of parasites, route planning and bike maintenance for a little while.

We hired bikes, visited ruins, ate in shabby restuarants and engaged in typical sibling banter and aggravation. Mild mortification swept over James and I whenever we removed our shoes in our shared bedroom during Dave’s visit; we may have adjusted to the foul smell of each other’s worn out kit but to Dave it was gag-inducing.

He wasn’t only subjected to our malodorous company; a Peruvian stomach bug hit him during his stay too and so we weren’t able to cycle for as much as we had planned. But the explosions from the bathroom when Dave was in there at least redressed the balance of shame when it came to embarrassing body odours. Thankfully, he overcame the worst of it for the highlight of the trip, an unforgettable visit to the Incan ruins at Machu Picchu.

It was great to see you bro, thanks for visiting…and for bringing a mountain of new kit for us too!

Sarah

(We’ve adjusted the photo settings on the blog so you can see larger versions of any of our photos. From now on just click on the image to enlarge it.)

The best way to catch up on news and family gossip after two years? Over burgers and beer of course!

Respect to Dave – we hire him a pretty awful bike and with no panniers, he carries everything in a 70l rucksack on his back and doesn’t complain once.

On a sunny Sunday afternoon, we time our arrival in the Sacred Valley just right. The feast of the Assumption is being celebrated in Calca and the whole town is out for the event…

It feels right to follow a traditional lengthy parade with some traditional Peruvian chicken. Every other doorway in Peru seems to be home to a polleria – a chicken restaurant. Before the main delight comes a bowl of soup usually with pasta, vegetables and sometimes various unidentifiable pieces of meat…James gets lucky with this one, which comes complete with a chicken foot – perfect for scratching that itchy nose.

Arrival in Ollantaytambo by lunchtime means we have time for an afternoon ride up to the ruins of Pumamarca…

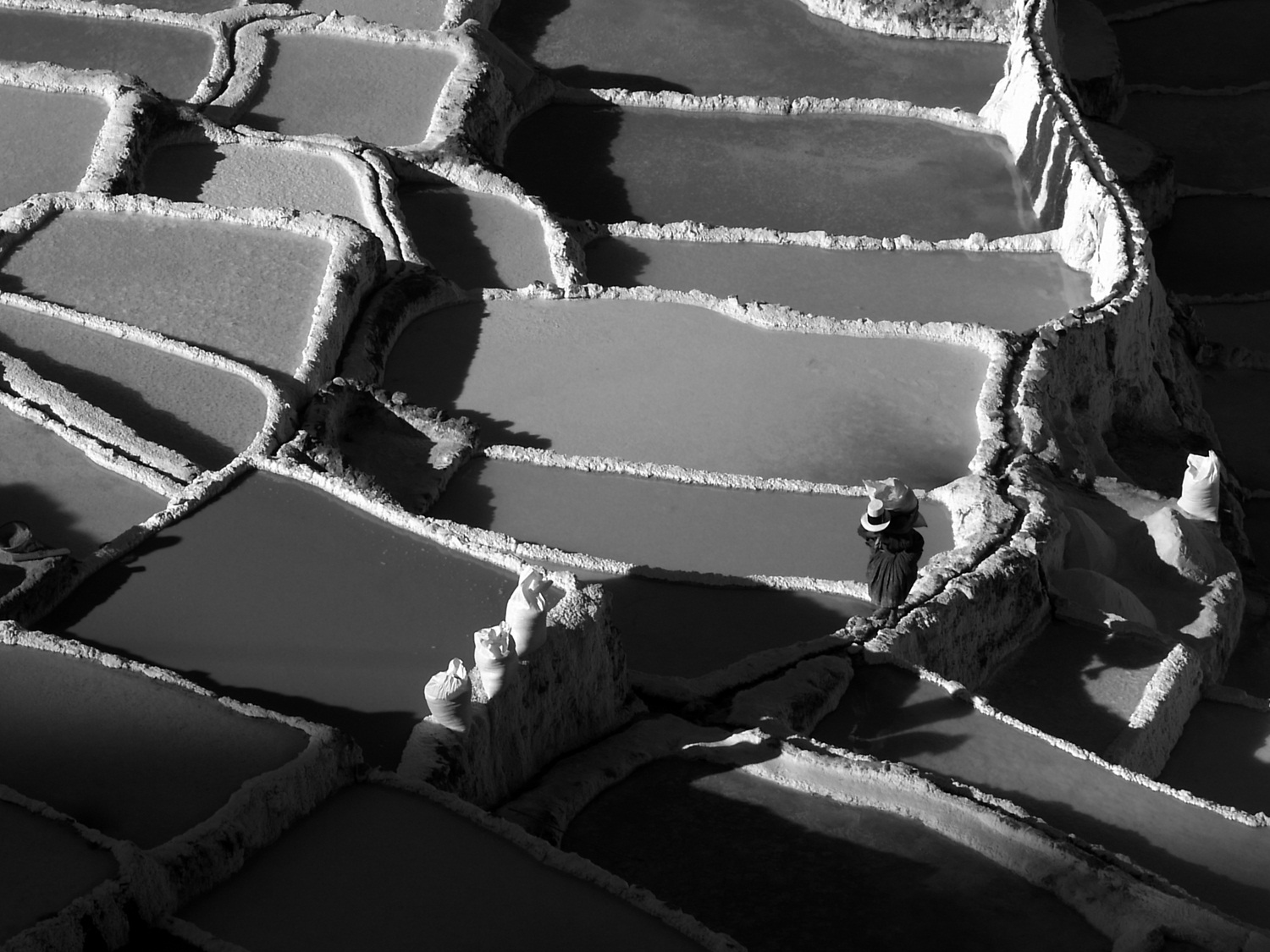

These pools collect water from a naturally salinated stream which was supposedly diverted by the Incas to harvest an abundant supply of salt for their royalty.

Now the salt pools are owned and worked by families around Maras. They still harvest the salt by hand and then haul it out in enormous sacks on their backs.

From Ollantaytambo, we choose the “cheapie” option to visit the ruins at Machu Picchu. The final section of the journey is a two hour walk to the town at the base of the ruins. Along train tracks through a lush green valley, it’s not an unpleasant way to spend a couple of hours.

This is as close we get to the train, which at its cheapest, costs five times the price of our bus/taxi/walk option.

Then after surviving the hideous tourist trap that is Aguas Calientes, it’s a lung-busting one hour steep hike to the ruins themselves very early the following morning. We arrive as the sun peeks through the clouds…

…providing an atmospheric first glance of this Incan city hidden in the mountains. The Spanish conquistadores could never locate it and it wasn’t rediscovered until 1911.

…to witness natural wonders – each of us could see our own shadow in the middle of this rainbow, a beautiful phenomenon which our photographer friend Skip identified as a Brocken Spectre.

…before the hoardes arrive and you can’t take a picture without at least another fifty or so people being a part of it (I wonder how many times we appeared in other people’s photos?).

…but we persevere and are rewarded. Bizarrely, the best Pisco Sours we find in Cusco are in a British pub! Chance to indulge in some good old-fashioned British pub games then…darts anyone?

Dave recruits Canadian Stephen to his team to pit himself in a battle of ’501 down’ against the resident cyclists. In what can only be described as a shifty move, the visitors emerge victorious. Rematch required.

Christmas comes early: Cusco kit swap

September 10th, 2013

If this journey has taught us one thing about kit over the past two years then it’s this: at some point, whatever the marketing hype and however much money you paid for it, it will break. Like our “expedition quality” Terra Nova Voyager XL tent, which fell apart in the Alaskan wilderness after just two weeks on the road. Or Sarah’s Rohloff – the “Rolls Royce” of gear hub systems no less – which had to be shipped to and from one of the only two places in the world where they could repair it when the hub bearings failed in Panamá.

It seems that when it comes to buying kit for really long trips, planning ahead for what happens when it breaks is probably just as important as how it actually works. Choosing kit that is as universal as possible – and so a lot easier to fix without shipping specialist parts around the world (ie, not a Rohloff) – is definitely a good start. One of my favourite things about Latin America is that the “fix it” culture which is fast disappearing from the supposedly developed world is still alive and kicking here. Whether it’s a failing tent zip, a beaten-up laptop, a seized bike part or a gaping shoe, head for the nearest market and chances are you’ll find a man or lady who can. These repair missions are always great fun too, taking us into parts of towns and cities where we otherwise would never have gone and meeting some incredibly helpful and skilled people. Time and time again on this trip, used and abused pieces of kit which we probably would have given up on long ago back home have been brought back to life.

However, there are still a few essential pieces of kit which we really have struggled to find on the road. Shipping spare parts around the world might seem like an attractive emergency option from the comfort of your home armchair, but in our experience it’s not quite that straightforward. Once you take into account the vagaries of Latin American postal systems, unexpected import taxes (try 40% in Colombia), and the difficulties of finding a secure address while on the move, it can work out much more frustrating and expensive than you might expect.

Enter stage left that long-standing lifeline of the kit-starved touring cyclist: the visit from family or friends. “We can’t wait to see you!” go the emails – and then, casually, as if it’s an after-thought – “Oh, and there might be just a couple of small things we need you to bring out for us – hope you don’t mind?” If you ever take up an invitation to visit a touring cyclist, just don’t expect to travel lightly. Chances are that by the time you set off to meet them, the “couple of small things” will have mutated into a full-blown expedition kit-list, and you’ll find yourself sawing the handle off your own toothbrush just to come in under your baggage weight limit.

For us, Dave’s visit to Cusco provided us with the perfect opportunity to replace a few of those hard-to-find parts, and to stock up on cold-weather gear for our next leg across the freezing Bolivian altiplano. Reports of night-time temperatures dropping to -20ºC from cyclists heading north had us scrambling to see if we could squeeze some new, warmer camping kit from the last drops of our kit budget.

And so, like a seasonally-challenged Santa Claus, our kit mule arrived in Cusco, heroically dragging behind him a sack of goodies…

James

Like any good Christmas, we began with some stocking fillers: a cyclist-sized Dairy Milk. Should keep our parasite friends happy for the next month…

…plus my special request: my first packet of salt and vinegar crisps in two years. Craving for Man Crisps suppressed for another year at least.

First priority was an overhaul of our camping kit. One by one, all four zips on our MSR Mutha Hubba tent had seized, calling for a serious of increasingly acrobatic manoeuvres to get in and out of the tent. We headed for a local seamster, who sewed in four chunky new zips and sliders in the time it probably would have taken us to unpick just one.

One too many shivering nights already in Peru had proved that our tired old sleeping bags weren’t really up to sub-zero temperatures. And so we decided to invest – two new Skyehigh 1000 bags from Alpkit, with a comfort rating of -13ºC. Not the lightest or most technical of bags, but more importantly they pack an impressive 1kg of down for a fraction of the price of the big brand names. As cold sleepers, somehow I don’t think we’ll be regretting these up on the Puna.

Next up, some extra insulation from the increasingly cold ground. Out with our trustworthy (but bulky) foam Ridgerests (a miserly 1.5cm thick), and in with two new Prolite Plus air mattresses (a luxurious 3.8cm thick). Meanwhile the old Ridgerests were put to good use…

…and recycled as perfect new protective cases for our Kindles and laptop. Lightweight, padded and made-to-measure – far better than anything you’ll find in the shops.

This is my second pair of Specialized Tahoe shoes so far on the trip. They’re a comfy compromise between trainers and “proper” bike shoes, but unfortunately have already started to split open at the sides. Luckily, shoe repair is easy to find in Peru – here a professional adds in the extra stitching that Specialized really should have put in from the start.

For a self-confessed friolenta (someone who feels the cold) like Bedders, it doesn’t get much better than hiding yourself in a down jacket – another Alpkit special. Somehow I get the feeling this might not be coming off much over the next 5 months…

…which is a shame when you’ve just invested in a new t-shirt as good as this one. Maybe I should put this publicly-pronounced love of the moustache to the test soon, just to complete my hideous facial hair quota for the trip.

A full drivetrain overhaul for the bikes: new front chainrings (after an impressive 25,000km), new rear sprockets (a lifespan of 12,000km with reversing) and new chains. Despite my moaning, Rohloff definitely has its advantages when it comes to easy maintenance – hopefully, these should see us through to Ushuaia and beyond.

After one soaking too many (and, if I’m honest, probably not enough Proofide), my trusty Brooks B17 had started to crack badly around a couple of rivets, and looked like it could tear off completely. Luckily, I found a leather craftsman who was able to replace the rusted rivet and apply a patch which hopefully will hold things together for a good while yet.

The most traumatic kit failure of the last few months was our beloved Primus Omnifuel stove. Two years of burning only petrol took its toll, seizing the control spindle and wrecking the thread. To their credit, Primus came good and sent us a new burner unit and spindle under guarantee – just unfortunately not in time for Dave to bring it out with him.

In the meantime, we had already been seduced by the shiny new titanium Primus Omnilite. Normally way out of our price range, incredibly we found it on special offer for the same price as a new standard Omnifuel, and snapped it up. This really is a dinky stove…

…but still with all the hallmarks of quality Primus construction. Looking forward to putting it to the test with some of that dirty Bolivian diesel.

After two years of stove-top coffee experimentation (with filters, “cowboy” style, brewed in a kids’ sock) – and having abandoned any pretensions of minimalism – we finally caved and bought ourselves a stove-top espresso maker. We might not fit in with the bikepacker crowd, but we can at least satisfy our morning caffeine cravings in style, and with a touch of crema…

Another over-worked piece of kit – our MSR MiniWorks water filter. When the ceramic filter starts to cave in the middle, like the one on the left, the bugs can start to get through and it’s time to change.

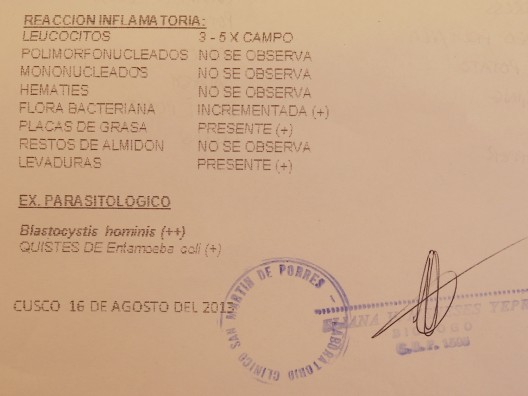

Speaking of which, Christmas wouldn’t be complete without the unwanted gifts. Our equivalent of the hideous knitted jumper from Great Aunt Matilda came in the form of a vicious return of our lingering parasitic friends, just as we were preparing to leave Cusco. This time we’ve really gone to war: a double dose of anti-parasitics, combined with a Hollywood-esque diet free from sugar, gluten, dairy and caffeine designed to starve them out at the same time. As I write this, we’re starting to feel better, and – fingers crossed – hope to finally be moving again soon.

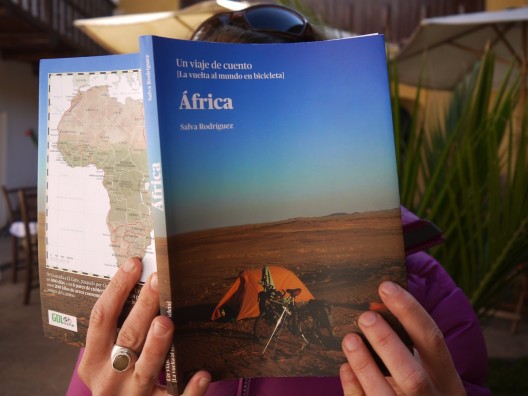

Every cloud has a silver lining however, and on the plus side it’s meant that we’ve got to share our extra Cusco downtime with our friend Salva and his girlfriend Lorelí. Plenty of time to get stuck into the excellent first book of his epic seven and a half year cycle round the world – leaving us itching all the more to get back on our bikes soon…

Leaving Cusco: an Andean antidote

September 20th, 2013

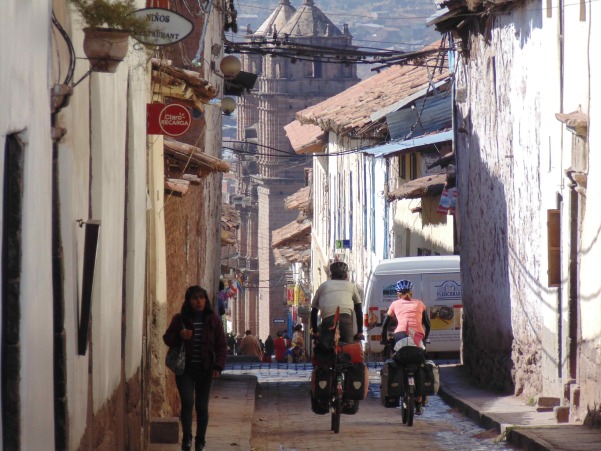

Having spent a month in the heaving streets of Cusco receiving visiting relatives and trying to repair our parasite-riddled bodies, finally it was time to leave fancy coffee, organised tours and Incan ruins behind and get back to some cycling.

Leaving Cusco was difficult in that we had to say goodbye to good friends and as always after extended time off the bikes, our legs had become soft, lazy and unwilling. The exit itself wasn’t without its challenges either. Leaving on the main road was ugly and not a route I would want to repeat in a hurry; red-mist descended quickly as Peruvian drivers proudly displayed their prowess in terrible driving, and both James and I came extremely close to losing both our tempers and our lives on more than one occasion.

Realising our mistake at spending more than five minutes on the main road, we turned off at the first opportunity and escaped back to our natural habitat – the campo. The Cusco antidote we had been looking for and our last foray into the Andes before the altiplano in Bolivia: fresh rarified air, legs burning at the first proper climb for five weeks, no traffic, snow-capped peaks, camping, speaking Spanish again…all of the ingredients needed to recharge the cycling batteries and shake off city life.

Sarah

…is to enjoy good coffee and flaky croissants at the French bakery on Avenida Tullamayo before we leave the city. Sadly the delicious breakfast can’t protect us from the carnage of the autopista…

…but soon we are off the main road and the only traffic we encounter around Acopia, and its four beautiful lakes, are bici-máquinas and donkeys.

On the pretext of admiring the view around the lakes, we stop frequently to rest our legs and take deep breaths.

Outside of Yanaoca, Marco (pictured right) screeches to a stop on his police motorbike to check we are OK and invites us to drop in at the police station to chat with him and his colleague Felipe…

…after cake and coffee with them, it’s clear we are not going any further that day. We set up the tent in the yard at the back of the police station but after much discussion amongst the force who decide it’s far too cold for us to sleep outside (despite our reassurances), we are ushered inside and given the honour of sleeping in the police dorm, in between official insignia stamped sheets and blankets.

The road turns to dirt after Yanaoca and offers the usual assortment of entertainment: alpacas so hairy they can barely see…

…and unexpected snacks – a lady stops us begging for a photo and in return gives us a bag of piping hot potatoes. Why anyone would want a photo of a sweaty gringo couple on their bikes is beyond me but the spuds are tasty. Peru has more than 150 varieties of potato of all colours, shapes and sizes…this pink one, teamed with salt and avocado, was delicious.

Back onto pavement briefly (joining a main road between Cusco and Arequipa) we hit dirt again and lots of flat, towards Hector Tejada…

A network of back roads in this area represents the chance to drop down to canyon country and Arequipa. Before we leave Cusco we toy with the idea of visiting the canyons, but have to abandon the idea when parasite destruction takes longer than expected. So from here, it’s straight ahead to Jauni and leave the canyon riding until next time.

We are again ushered indoors for the night when we reach the village of Jauni. Shopkeeper and generally lovely lady, Francisca, offers us a room at the back of her house…

The next morning we emerge into fierce sunshine to share freshly boiled eggs and chat with Francisca…

Land provides shelter – most houses here are made from mud taken directly from the earth – we pass hundreds of hand-made bricks laid out to dry in the sun.

A pleasant 7km downhill gets her from home to school in no time, but I imagine her return journey isn’t as much fun.

Our final major climb in Peru is a lung-buster and only the llamas are really accustomed to life at this height.

In Vilavila, the schoolkids want to know all about our water filter. James cruelly plays on their innocence telling them that you put water in and get chocomilk out; they are crushed when they learn the boring truth!

As always, cake is never far from our minds. A long valley ride towards Lampa, reveals rock formations that clearly resemble the firm favourite and much-missed lemon drizzle (we’re blaming you for that, Lars!)

We reach the altiplano just before Lampa, and there’s nothing but straight lines and our own shadows to keep us company.

Small, pretty and friendly it’s not hard to choose Lampa over the nearby city of Juliaca as our base for arranging our Peruvian exit visa…

…and taking a closer look at the stunning church in the square, before setting off again towards Lake Titicaca and the Peruvian/Bolivian border.

Route notes

From Cusco, we took the pista south towards Juliaca, turning off just before Checacupe. We rode towards Acopia and onto a network of back roads to Lampa via Yanaoca, El Descanso, Hector Tejada (aka Pallapata), Jauni, Cacycho, Vilavila, Palca and then Lampa. It’s a mixture of paved and good dirt, with the main pass just before Vilavila. From there it’s onto the altiplano, and flat and fast to Lampa. Our total distance from Cusco to Lampa was 413km, and took us 5½ days riding.

Lake Titicaca – and Bolivia by the back door

October 1st, 2013

As we reshuffled our idea of descending into Arequipa’s canyons due to lack of time, our exit from Peru suddenly included visiting the famous Lake Titicaca. Sitting astride Peru’s and Bolivia’s border, the local joke goes something along the lines of “Peru got the titi and Bolivia got the caca” but our trip around the lake was equally enjoyable on both sides.

There is no immigration control on the far side of the lake, so from Lampa, we travelled by bus to get our passports stamped in Puno (more details at the end of this post) before visiting the Capachica peninsula and then riding the eastern side of the lake on quieter roads to the border at Tilali.

Sarah & James

Our “high tech” map of the Capachica Peninsula (with our route marked in pink) which reaches out into the lake just to the east of Juliaca. We spend a few days here before heading towards Bolivia…

…but to get there, first we have to ride past this. Stretching out of Juliaca on the windswept altiplano is 15-20km of rubbish. Some brave souls sift through it for treasures to keep and sell but mostly it’s broken tvs and used nappies.

After riding through the town of Capachica, we reach a gate shaped as the hat typical to this region and we know we have arrived at the lake…

A rest day is prescribed and we pitch the tent at Kawai homestay near Llachón, overlooking the lake and back towards Puno…

Kawai homestay: Magno and his family provide accomodation and tasty local meals overlooking the lake, just outside of the village of Llachón.

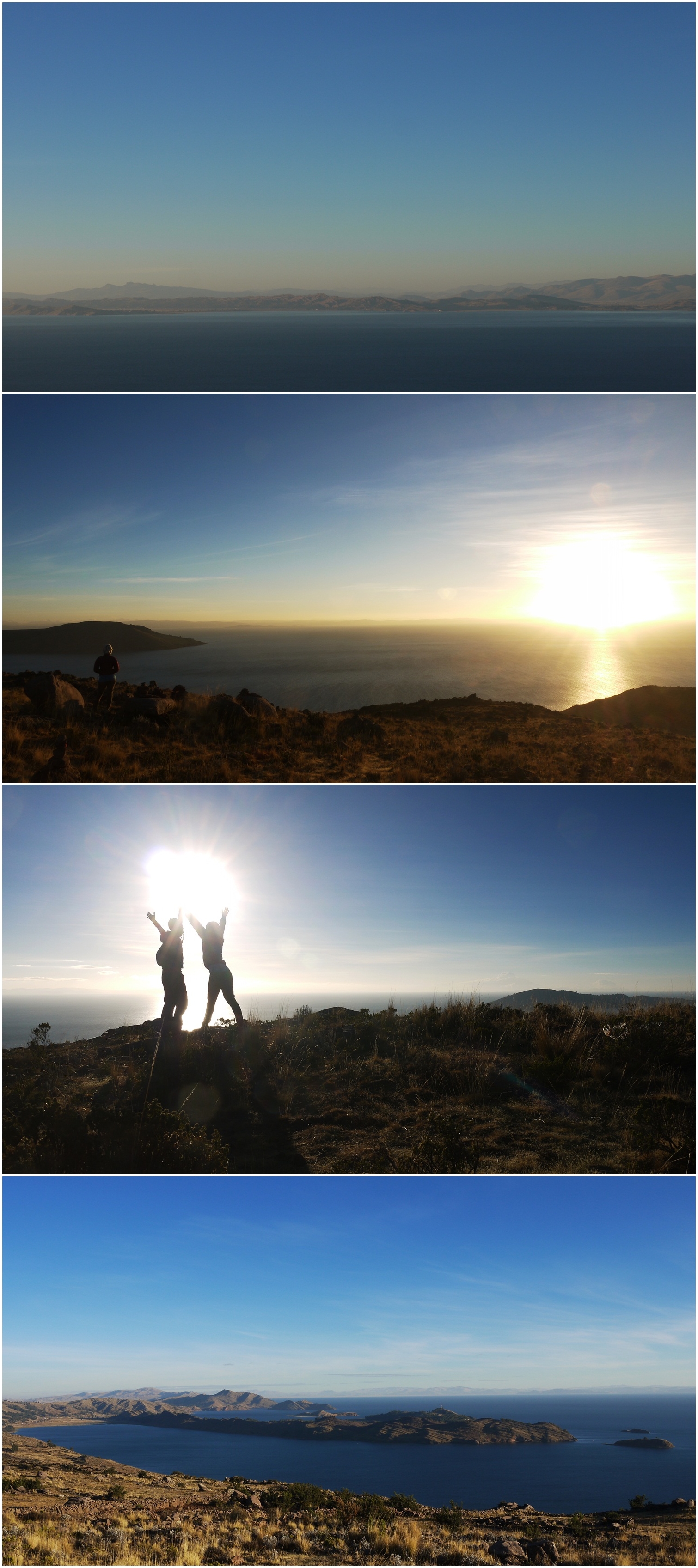

We drag ourselves out of the tent at 0430 and up to the highest point of the peninsula to see the sun rise over the lake. The magnificent views are more than enough reward for the effort – thanks for the tip Alfie!

And we still make it back to the homestay in time for delicious fresh doughnuts and jam for breakfast.

A leisurely ride around the rest of the peninsula and we are at Playa Chifrón just in time for lunch on the beach…

Riding away from the peninsula towards Escallani, we follow a wonderful dirt road that hugs the coastline…

…and the boats are out collecting totora; the prolific reed that grows on the shore is used for everything from eating to weaving to animal fodder.

The people of Huancané, upset with their corrupt mayor, lay a road block in protest. Thankfully cyclists are allowed through…

…and we reach the “other” side of the lake. Little traffic and beautiful views make it the perfect way to leave Peru.

…nothing for it but to get stuck in. It freezes my brain! I am really not a fan of jumping into cold water but I can’t just sit on the beach and observe; this is Lake Titicaca after all.

We warm back up in the sun and enjoy sweet granadillas; this kind of tropical fruit will be harder to come by in Bolivia, we are told, so we eat as much as we can in our last few days in Peru.

After passing the police checkpoint at Tilali, Peru has one tough climb left for us. I grumble all the way up and vow to make a case to the Office of International Border Crossings (there must be one, right?) that they do not always have to choose difficult dirt climbs to mark the territories between countries…or perhaps it’s just the particular borders we choose to cross at?

There’s no one else up here, just hundreds of empty buildings that are used on Wednesdays and Saturdays for a huge contraband market.

No-man’s land (and the climbing) continues much further than I anticipate; it’s an 18km slog from Tilali to Puerto Acosta, the first town on the Bolivian side. We arrive shattered and seek out dinner…

…which we find at a kiosko in a deserted square. First food impressions are positive: hot hearty soup followed by a heaped plate of rice, potatoes and minced beef for just over US$1. Exactly what is needed.

Our first impressions of Puerto Acosta on the otherhand are pretty bleak – we arrive as it’s getting dark and there is a bitter wind blowing around a town where seemingly no one lives. The following morning both the people and the sun emerge and it’s a much nicer place to be.

And our first impressions of bananas – the crucial staple food of cyclists – they’re cheap, really cheap. In Escoma, 4 bananas costs us 1 Boliviano…in sterling, that’s 44 bananas for £1!

We continue to follow the lake on the Bolivian side, through peaceful villages where running is a rarity…

…on to Ancoraimes, now truly on the altiplano, where bicycles are the most common form of transport. We get swallowed up in the school commute.

Ché propoganda reappears reminding us of our month in Cuba, nearly two years ago. His final guerilla campaign took place in Bolivia before he was captured and shot by the Bolivian army and CIA at Villagrande; his iconic face can be found everywhere here.

…and encounter more locals who opt for cycle transport. This cholita with trademark bowler hat balanced precariously and pleated skirt flowing, does her shopping by bike.

We make it to El Alto (the city above La Paz) in no time, practically free-wheeling along the pancake-flat altiplano. At the border between El Alto and La Paz known as La Ceja (“The Eyebrow”) we are treated to an unforgettable first view of the city with the snow capped peak of Illimani in the background. Time for a few days off to gather ourselves before we head back out onto the altiplano…

Route notes:

We followed the excellent information on Bicycle Nomad and from Harriet and Neil on the Andes by Bike blogs – here are a few additions and updates:

Lampa (35km NW of Juliaca on the secondary routes to and from Cusco) is undoubtedly a more pleasant base than Juliaca for the immigration trip to Puno. It’s 1½ hours each way in combi from Lampa – Puno with a change in Juliaca.

Peruvian immigration:

In Puno we were given our Peru exit stamp dated for that day. According to the immigration agreements between Peru and Bolivia, we were then told that we had to present ourselves to Bolivian immigration within 7 days. This was plenty of time to get to Puerto Acosta, even with our Capachica Peninsula detour.

Capachica Peninsula:

To access Capachica, ask in Juliaca for the road to Coata. The most spectacular section of the loop was the cliff-top ride from Chillora to Escallani on the eastern side, en-route to the main Juliaca-Huancané road at Taraco.

To take the coastal road from Moho (highly recommended), ask for the paved road to Tilani via Conima (38km total Moho-Tilali). Leaving Tilali, you pass through a final police checkpoint, and then climb up to the border line by the smugglers’ market. From here it’s a rough climb and descent into P.Acosta (18km total Tilali-P.Acosta).

Bolivian Immigration:

We were given a 30 day tourist visa in P.Acosta. We tried to get this extended to 90 days (apparently this is easy at more major crossings), but were told we had to go to La Paz to do this – which we did, free of charge and with no hassle.

Our total distance from Lampa-La Paz was 502km (it would have been 386km without the Capachica detour), and took us 6 days riding.

A Peruvian A-Z

October 10th, 2013

Ah, Peru. How we loved you, and – just occasionally – how we loved to moan about you. Peru will stick in the memory as a real montaña rusa (rollercoaster) of a country, giving us some of our biggest highs – both literal and metaphorical – as well as some of our most grumpy lows of the trip so far.

In riding terms, it will be hard to beat this country for the sheer variety of its incredible landscapes. Peru has it all, often compressed into a single day’s ride: the lush gorges and hilltop fortresses of Chachapoyas; the arid, Star Wars-esque canyons of Cajamarca; the starkly beautiful altiplano and lakes of Junín and Titicaca; and of course the snow-capped peaks of the Cordillera Blanca. And we didn’t even scratch the surface of this enormous country – by sticking stubbornly to the central ranges of the Andes we bypassed the Peruvian Amazon, the pre-Incan ruins of the coast, and the deep canyons and high volcanoes of Arequipa. If you like to go slow like we do, then even four months on a bike in Peru will leave you feeling like you’ve missed out.

But if Peru was at the front of the queue on the day when the natural spoils of South America were awarded, then there were times when we couldn’t help thinking it was stuck at the back (or maybe just didn’t bother turning up) when the personal charm and warmth were handed out. It’s not that we didn’t meet friendly, hospitable people. As always, away from the main roads and tourist honey pots and out on the back roads of the campo, we were grateful to the many Peruvians who helped us on our way with gifts of food, drink or a spot to camp for the night.

Yet there was still something missing: that magical human element, so hard to put your finger on, but which has been at the heart of some of our best experiences of the trip so far. Call us spoilt, but in Peru we missed that irresistible Latin American lust for life that we had come to love from some of our favourite countries so far. The spontaneous roadside encounters that send you on your way with a grin on your face. The random chats with curious old men about everything from left-wing politics to this year’s potato harvest, via The Beatles and Mr Bean. That sense that however bad things get, the best way to deal with it is to laugh, joke and dance your cares away with closely-knit family and friends. We’d grown used to life in Latin America being lived in full colour, but at times in Peru it felt like someone had flicked the switch into shades of grey.

It’s always telling to hear how people describe their own countries to you. In Colombia, a country where the last 50 years of civil war have left an estimated 220,000 people dead and up to 5.5 million displaced, people still never tired of telling us how blessed they were to be living in “paradise”. In Ecuador, people proudly told us of the steps forward their country has taken in the last few years under the leadership of President Rafael Correa. And in Peru? “Watch out for the ratones“, they told us over and over again: “This country is full of thieves.”

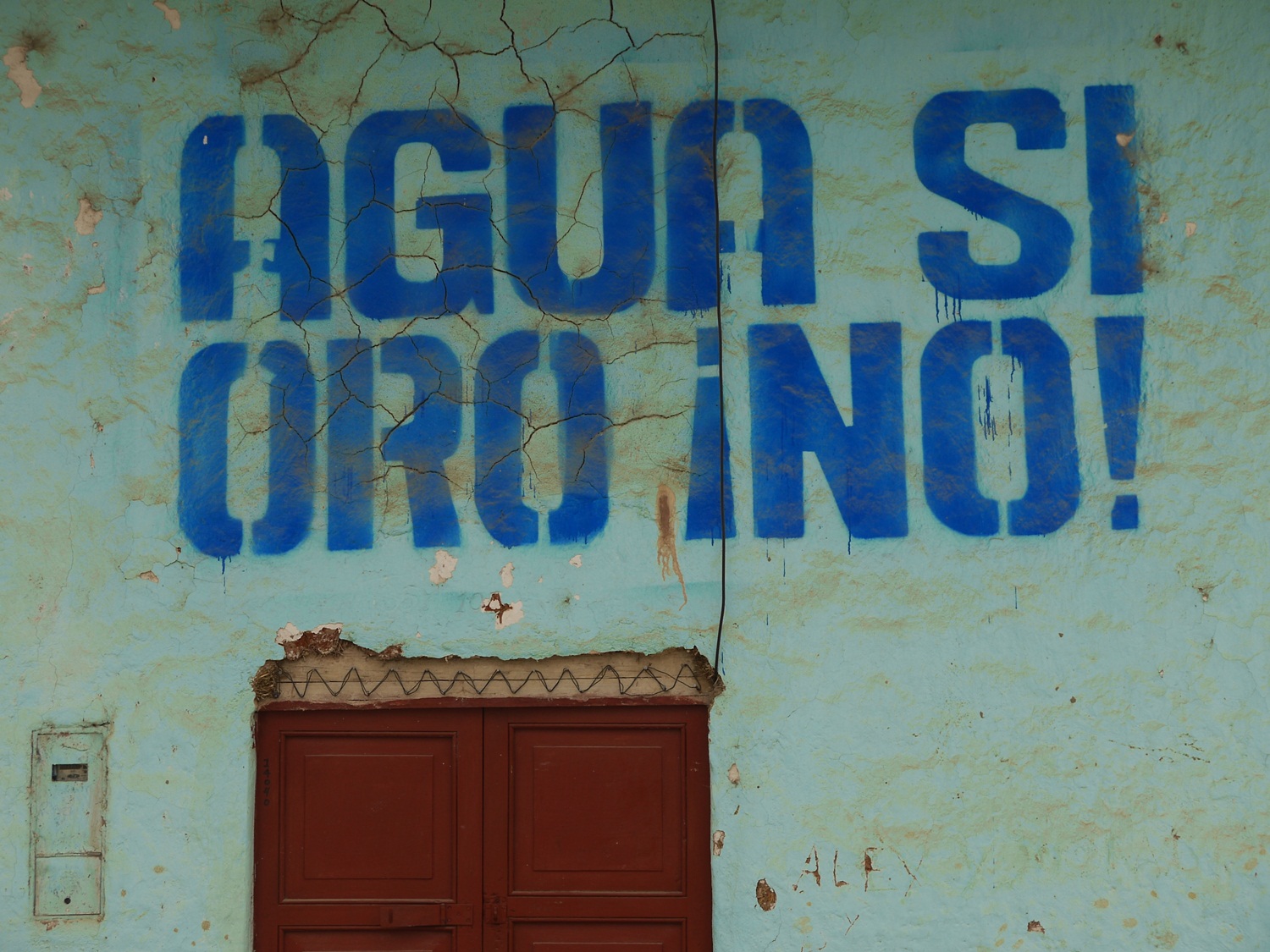

And to be honest, you can hardly blame them. Of all the countries in Latin America, Peru’s mineral wealth has meant that it has perhaps suffered most from foreign pillaging – firstly at the brutal hands of the conquistadores, and then more recently at the more airbrushed (but ultimately no less brutal) hands of foreign mining companies. Peru is one of the world’s richest countries in terms of natural resources, but of course the average Peruvian sees none of this wealth. After centuries of exploitation, life here remains undeniably tough. It’s no surprise then that most Peruvians are ambiguous at best about the most recent influx of foreign invaders, this time clutching digital cameras and sporting matching “I’ve been to Machu Picchu” hats. Tourism might have become a mainstay of the economy, but that doesn’t mean Peruvians are about to start receiving us with hugs and kisses.

Nevertheless, our four months in Peru will undoubtedly go down as some of the most memorable of our trip. Peru made our knees go weak with its climbs, our fists clench from time to time with its very un-Latin American miserablism, and our jaws regularly hit the floor at its amazing landscapes. Summing it all up is pretty much impossible, so in the spirit of our Mexico A-Z, here are some of our most memorable Peruvian moments in (sometimes highly dubious) alphabetical order.

James

Andes. For us, Peru was all about the Andes – and this was the moment we knew that we had arrived: gazing down at our 60km, almost three vertical kilometre descent to Balsas and the next day’s 45km climb to Celendín. After a while, spending two days climbing a mountain followed by two hours freewheeling down the other side became quite normal…

Butchers Bike. Markets are always the first place we head for in a new town, and Peru had some of the best we had seen since Mexico. Hang around the entrance and you’ll find the true bike heroes of Latin America, transporting everything from mountains of mandarins to a pile of freshly slaughtered goats by pedal power.

Cordillera Blanca. If we’re honest, then this was what we were really waiting for in Peru – and we weren’t disappointed. Our loop around Punta Olímpica and the Portachuelo de Llanganuco went straight into our top five rides of the trip so far and to the top of our list of places to return.

Dreadlocked. We might have been far from the Caribbean, but dreds are all the rage amongst the farm animals of rural Peru. Most were dogs, but this donkey was a show-stopper.

Eating etiquette. We quickly learnt that mealtimes in Peru have a strict etiquette. Step 1: Soup. Crouch low over bowl and spoon it in as quickly as possible. Step 2: Main dish. Maintaining piece of chicken in one hand, stare vacantly at large screen TV (ensure volume at maximum) while shovelling in rice. Note: Avoid eye contact with other patrons at all times, and never betray any pleasure in the process of eating.

“De Freeeeeente!” It didn’t seem to matter where we were heading in Peru, the directions were always the same. “De Frente!” (“Straight ahead!”) they would say – even when we were standing at a junction with our only options being to turn left or right. No wonder it took us four months to get across Peru…

“Griiiiiiiingo!” Forget Andean music, this was the real soundtrack to Peru, shouted from the roadside and from passing cars wherever we went, accompanied by giggles and hoots of laughter once we were safely past. Cyclists – especially Europeans – tend to get their knickers in a twist about it, but resistence is useless: in Peru, if you’re not Peruvian, then you’re a gringo. It might not win them any prizes for geographical knowledge, but at least it was usually accompanied by smiles and waves.

Hunched abuelitas. For some people, it’s the stray dogs in Peru that break their heart. For us, it was the abuelitas (old ladies) that we wanted to scoop up and take home: toothless, bent double under an enormous bundle of firewood, leading a flock of sheep, cattle, llamas and pigs home for the night and spinning wool as they go. This is rural, highland Peru – a life of harsh poverty and little opportunity, unchanged for hundreds of years.

Inescapable. “Just wait for Peru”, people told us when we moaned about the lack of food flavour ever since Mexico. “It’s the culinary capital of South America”. And what did we find? Chicken. Everywhere – for breakfast, lunch and dinner. To be fair, in between the chicken, there were a few food highlights, but in general Peru failed to break the “filling but bland” Latin-American mould, and was something of a food anti-climax.

Jelly. And the ubiquitous Peruvian sweetner to follow the chicken? Jelly, of course. We never quite worked out why: was it just that Peruvians never grew out of the kids’ birthday party habit? Or was it the general lack of teeth in the Peruvian population that made it such a food favourite? Either way…

Kuelap. Away from the crowds and manicured lawns of Machu Picchu and the Sacred Valley, this was our favourite ruin in one of our favourte parts of Peru – the misty valleys of Chachapoyas, in the north. Abandoned to nature, and with an incredible 360 degree view into the valleys below, you really could imagine back to when this was a pre-Incan hilltop fortress.

Lakes. Peru had an incredible variety of lakes of all sizes and types: from the icy turquoise of Laguna Parón in the Cordillera Blanca…

…to the slightly warmer blues of Lago Titicaca on the southern altiplano – where at times you could almost forget you were four vertical kilometres above sea level, and convince yourself you were actually pedalling along the shores of the Mediterranean.

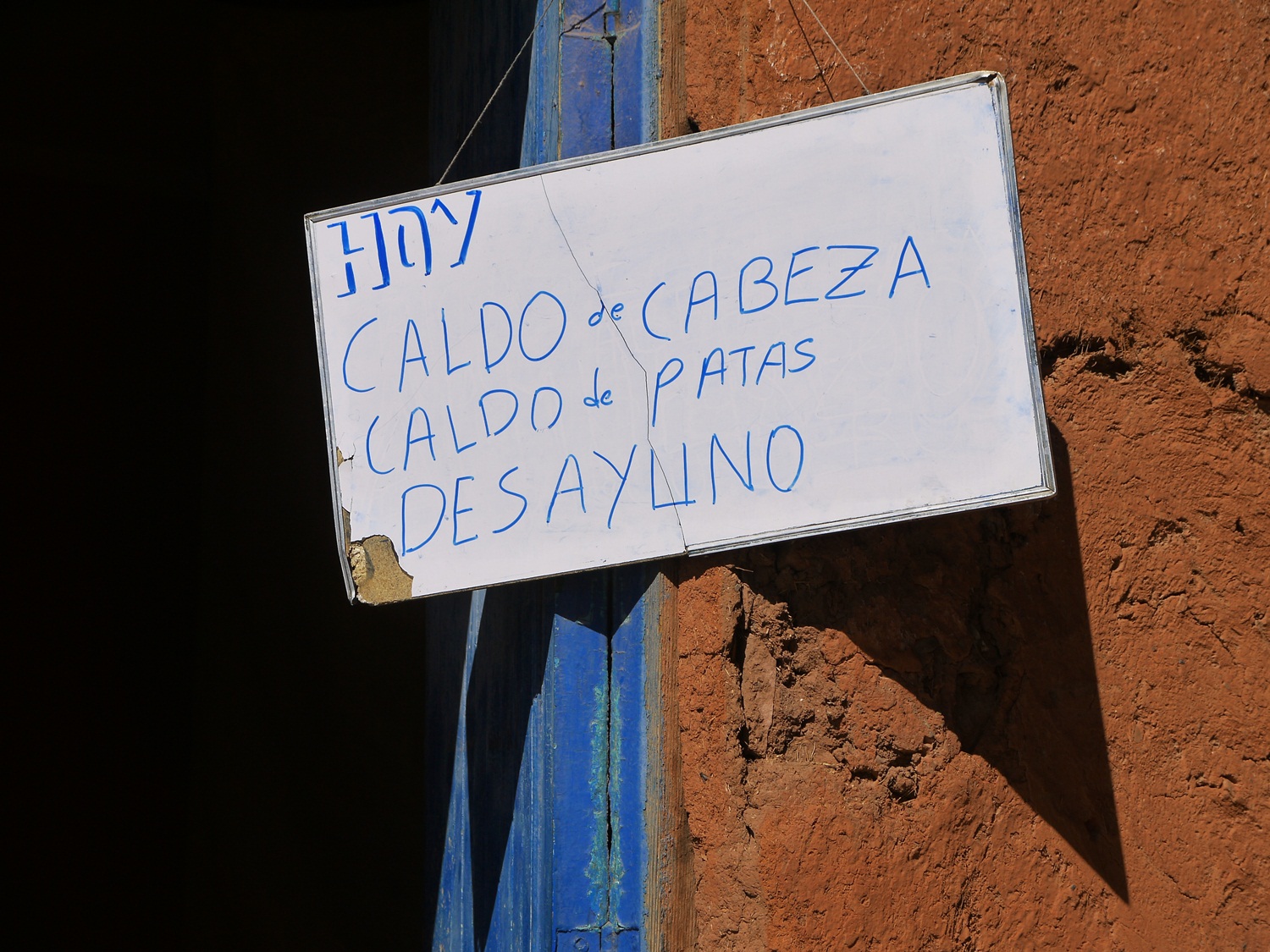

Menú. Bland it may have often been, but for calories-for-cash value it was hard to turn down the Peruvian menú: a lunch of soup, a mountain of rice, chicken (of course) and a drink for less than US$2. Breakfast, on the other hand, was easy to pass by – faced with a choice like this between “cow’s head soup” or “cow’s hoof soup”, even our increasingly tedious breakfast porridge routine suddenly became appetising once again…

“No hay!” While we met plenty of smiling, friendly people in Peru, “No hay!” (“We haven’t got any!”) was its counterpoint – barked moodily from behind shop counters and hotel receptions. This was definitely the first place in Latin America where we’d seen a government campaign like this one having to remind people that “when you treat a tourist well, you’re treating Peru well.”

Oro. “Yes to water, no to gold!” – so say the residents of Cajamarca, where a massive new mining project threatens to pollute their precious water supply. Since the time of the Spanish conquest, mining has been a topic of furious debate in Peru – it might bring in much-needed foreign investment, but continues to leave behind massive environmental and social problems for local people.

Palta. For the days when we couldn’t face menú just before an all-afternoon climb, there was always palta (avocado) – and Peru had some of the best we’ve eaten on the whole trip. This really is a food of the gods – rich, filling and full of healthy fats. I’m just not sure we will ever re-adjust to the expensive, hard golf balls that pass for avocados at home…

Que en paz descanse (“RIP”). “I ride with Jesus, and if I don’t come back I’ve gone with him”, say the window stickers on Peruvian minibuses, in one stroke absolving their drivers of any responsibility for their driving. If they were more honest, they should probably read: “I drive like a cretin, and if I don’t come back it’s probably because I’ve driven myself and my passengers off the edge of a cliff while overtaking on a blind bend at 100km/h.” Peruvians’ erratic driving may have brought on the red mist every time we misguidedly ventured onto a main road, but more than that it made us incredibly sad to see so many Peruvians needlessly killing each other.

Rush hour. Away from the blaring horns and slalom course of the main roads, rush hour on the Peruvian back roads was of a more sedate kind, as people led enormous mixed groups of llamas, alpacas, sheep and pigs back from the fields for the day. This was undoubtedly my favourite Peruvian “long vehicle”: a donkey leading a pig home for the night as if it was the most natural thing in the world, its owner nowhere to be seen.

Sociable. Our ride through Peru coincided with the peak season for cyclists heading south, making it a sociable place to catch up with new and old friends from the road – focused of course on eating and drinking: trufa munching with the French tandem duo Artur and Caro; more caffeine hunting with our friend Anna; polishing off our Dairy Milk supply with the Genners; and Spanish tortilla making with Salva and his girlfriend Lorelí.

Tea. Of course, for us no country since Mexico would be complete without at least one attack from our parasite friends forcing us off the bike. On long bike trips, some people suffer with bikes that fall apart, while others struggle with injuries. It seems that our weak point is our stomachs, which stubbornly refuse to adapt to foreign invaders in the way our legs have to all-day climbs. Luckily Peru had an abundance of stomach-calming manazanilla (camomile) to sooth our stomachs and keep us pedalling.

U-shaped. Peru: land of the switchback. Where Ecuador goes for direct and steep when faced with a mountain to climb, Peru goes for long and spaghetti-like – making for steady climbs and long descents with plenty of time to take in the views. This was one of our favourites, descending from Pallasca into the Río Santo gorge in northern Peru.

Vote for me. In Peru – like much of Latin America – you’ll struggle to find an abandoned building or wall which doesn’t feature a sign urging you to vote for Edwin, Alan or Alvaro. Except the uniquely Peruvian twist on political propaganda is that each candidate chooses an image to represent their campaign – ranging from a sombrero to a bulldozer to one of our favourites, this llama.

White flag. No, not the white flag of surrender when faced with another monster Peruvian climb, but one of salvation for the hungry cyclist. We quickly learned that a white flag hanging outside a house in rural Peru meant that they had freshly baked bread for sale – a lifeline when often the only thing the tiny local shops had on offer was out-of-date crackers and yesterday’s jelly.

X-rated. Finally, we ticked the “night in a love motel” off our Latin American to do list – and we didn’t even have to pay for it. When we presented ourselves to the chief of police in Bagua Grande and asked if we could sleep on his floor, he insisted on sending us to the local love motel at his expense. Jacuzzi, TV, flashing lights – this room had it all, even if our feet did hang off the end of the heart-shaped bed…

“You wouldn’t want to live here” is a phrase that has run through my head many times on this trip, but maybe none more so than in Peru. This is a country of ghost towns – neglected, wind-swept and strewn with tumbleweed. Cycling through places like this, with the barefoot children of one or two remaining residents watching silently from the doorway, makes you realise that opportunity is one of life’s greatest riches. Most of these people will never have the opportunities we take for granted – to travel, to study and to work.

Zzzz. Peru had some of our most idyllic camping spots of the trip so far: the pampas of the Cordillera Blanca with peaks towering above; breakfast on the shore of Lake Junín while watching feeding flamingos; and early morning views across Lake Titicaca from the Llachón Peninsula. Five star accommodation doesn’t get any better than this.